Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

Creativity: The unexpected science skill

Scientist may not be the first profession that comes to mind when thinking of a "creative" career. Vocations like artist, cinematographer, photographer, or novelist may fall much higher on the list. But creativity is a highly underrated research skill, which has become more clear to me as I transition back into academia.

For my ecological systems class, one of our first readings was Stuart G. Fisher’s “Creativity, idea generation, and the functional morphology of streams.” Fisher, an emeritus professor from Arizona State University, who published the article in the Journal of the North American Benthological Society, focuses on the accessibility of creativity and how to hone, develop, and apply it just like any other tool or skill. I’ve always enjoyed exercising my creativity through hobbies and personal projects, so the opportunity to practice creativity to direct my research questions intrigued me.

My research focuses on advancing environmental DNA (eDNA) use in monitoring fish populations. Just as humans leave DNA in their environment, like hair and skin cells, so do fish. Fish shed DNA through their waste, scales, and eggs, among other pathways. This DNA can float around in the water for anywhere between 48 to 72 hours. By collecting water and testing for DNA of different important fish populations, we can learn if those species are present in that area, or not. The use of eDNA in fisheries management is new, so there are a lot of opportunities for new ideas.

Fisher’s paper discusses how to creatively approach research to generate new ideas and questions. I have found these helpful as I begin to learn more about my research. Fisher outlines four stages of creation: preparation, incubation, illumination, and verification. Graduate students are quite familiar with the preparation stage as we take classes to enhance our understanding of a broad range of subjects that could be applicable to our research. The incubation stage happens subconsciously. The ideas and information mull around in your brain until…illumination! That’s the “a-ha” moment where an idea seems to gel in your head out of nowhere. Finally, verification is the step of idea refinement and elaboration. Fisher discusses how this process can be enhanced nurturing creativity; he mentions five criteria:

- A sound, broad education extending into related disciplines

- Varied experiential activity

- An understanding of the structure of existing theory around your area of interest

- Self-awareness to recognize intuition and its products

- An intellectual environment where new ideas are welcome

I now recognize how these criteria align closely with the goals of graduate study and how they align with my own personal goals. While these aren’t necessarily criteria you can incorporate into your job today, Fisher also provides exercises he used with students to foster and apply creativity. One exercise you might try out is the deliberate juxtaposition of distantly related observations or ideas.

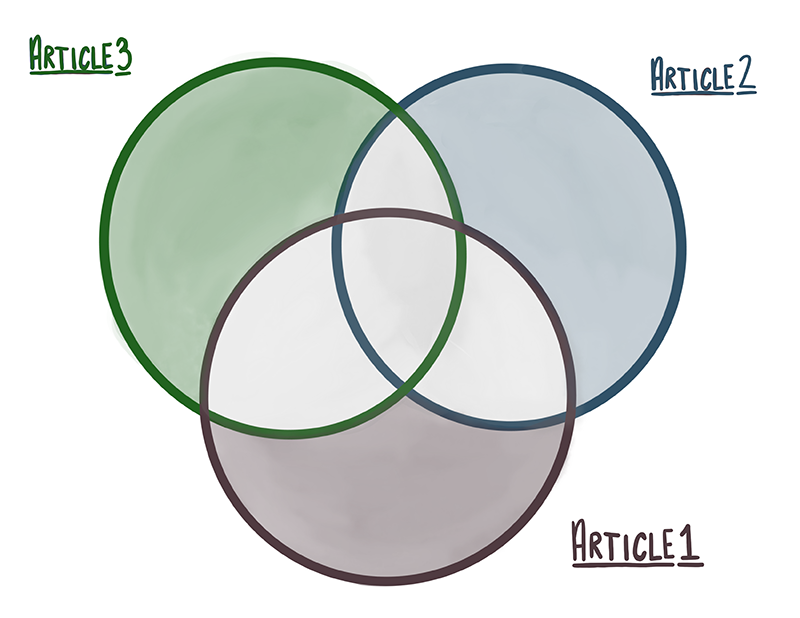

Fisher uses a Venn diagram to juxtapose seemingly unrelated and random research and generate new ways of thinking about stream ecology. He challenges his students to juxtapose random scientific papers to their own research questions to stimulate ideas and conversation through his diagram. I now use this practice when I read about new research. I challenge myself by asking, “How might this fit into my questions?.”

This activity can be as simple as navigating to your favorite new source and reading material from three different sections and assigning each a circle on a Venn diagram. You can summarize your articles in each circle and then think critically about the material and how the content of one may relate to another or an overarching topic of interest. Creativity is useful everywhere! Thinking about something familiar in a new way can be exciting and engaging.

Reference:

Fisher, Stuart G. "Creativity, idea generation, and the functional morphology of streams." Journal of the North American Benthological Society 16.2 (1997): 305-318.

Photo, top left: The Choptank River is one of many waterways in the Chesapeake Bay watershed that anadromous fish during spawning seasons. Anadromous fishes spend most of their adult life in the ocean and travel upstream to their natal streams to spawn. Credit: Chelsea Fowler

See all posts to the Fellowship Experiences blog