Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

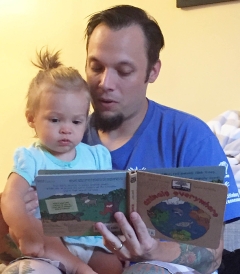

Learning On The Job How To Be A Sociologist — And A Father

Before starting graduate school, I was convinced that learning to be a sociologist and getting a Ph.D. would be a matter of mastering the texts assigned in seminars or recommended in lectures. It never occurred to me that doing research — the actual practice — would teach me the most about my chosen field. In fact, the texts provided only a superficial sense of what it means to be a sociologist.

One thing you do a lot of as a sociologist is conduct formal interviews to collect data. Years ago, when I first went into the field to work on my master’s thesis, I found that if I was anxious or nervous about doing an interview, it would show. When trying to ask follow-up questions about something interesting, sometimes I’d phrase the question oddly or miss the mark completely. Then the opportunity to get richer interview data would pass.

It took time and practice to learn how to do an effective interview. While the books and articles on how to conduct sociological interviews provide some insight about how you should phrase a question — for example, when to be assertive and when to take a disinterested tone — they simply fail to provide those skills via the text alone. For me, learning how to be a father has followed the same process.

The parallels between learning to be a scientist and becoming a father are stark, a fact that soon became clear after my daughter, Brody, was born in May 2015. A lot of this parenting thing has felt the same as being a graduate student: on-the-job training. I’m not ashamed to admit that half the time I feel like I’m winging it (fatherhood and studenthood).

The parenting books I studied provided a sense of what to expect, which alleviated some of the anxiety I was feeling. One of the common mantras in those parenting books is to talk to your children as much as you can, so I made it a point to read to Brody early and often.

I thought a lot about what to say to her and how to say it, but it wasn’t always clear to me that she was listening. But she was watching. The more I noticed her imitating me — especially those gestures and tones of voice I do without much thought — the more I realized how true is the saying, “Their brains are like little sponges.”

Once not long ago, I watched her sternly point at our dogs and say, “Sit!” although her cute little voice failed to convey any true sense of authority. I was tickled to see one of the dogs actually obey her command, but I was also a little shocked. Not once did we “practice” doing that. No flash cards, no board books, no puzzle games, and no educational toys had instructed: “Point your finger like so, look at the dogs, tell them ‘sit,’ and be firm about it.”

She’s learning as she goes, just as I have in grad school and as a father. While I try to incorporate those things I learn on-the-job into my daily practice, whether it is researching or parenting, I have come to realize that no amount of reading will ever be enough. To really know how to be a parent, or a sociologist, you have to actually try it — to put abstract practices and principles into action. Some things will work, some won’t, and knowing the difference, for me, has been a matter of experience.

Photo, top of page: William Yagatich with daughter Brody, then 15 months old. Credit: William Yagatich.

See all posts to the Fellowship Experiences blog