Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

Oysters Do More for the Chesapeake Than You Might Think

For the past two years, I’ve traveled tidewater Maryland, asking people, “why aquaculture?” I ask entrepreneurs why they decided to get involved in growing oysters in tanks or floats in the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries. And for the commercial fishermen who aren’t, I ask, “why not?” This very basic question begins the discussion with each person I talk to, in order to understand on a larger level what motivates individuals towards or away from oyster aquaculture.

When I began interviews, I had a few ideas about why people might be interested in or wary of oyster aquaculture. For centuries, Maryland had a wild fishery, and still does. But growing oysters in cages and floats became legal in every Maryland county in 2009, and in the decade since, many entrepreneurs and some commercial watermen have taken the plunge. A change in the law, coupled with advances in disease-resistant oysters that grow quickly in our estuarine waters, helped push the industry forward. But some have been resistant — aquaculture has not taken off in Maryland as fast as it has in Virginia in recent years.

What are the reasons for reluctance? I thought money might be a big one — both the ability to make money from farming oysters as well as the money needed to start your own oyster farming business. I also wondered how much the ecological role played by oysters influenced individuals who have entered the aquaculture industry. Are people getting into oyster aquaculture because it’s a ‘green’ business?

You may already know about the beneficial things oysters do. They filter the water, contributing to a “cleaner” bay, because they ingest the nitrogen and phosphorus entering the waterway. They provide habitat, creating homes and hiding places for all sorts of small critters. They deliver a benthic buffet, serving as a food source themselves and providing refuge for many other animals that the Chesapeake food web depends upon. These benefits oysters provide for their ecosystem or more aptly, their social-ecological system (a term that recognizes the human role in an ecosystem), are called ecosystem services.

Ecosystem services describe the benefits people receive from a system. The ecosystem services framework helps put a dollar value on just how much a healthy system (like the Chesapeake Bay, for example) may be worth when you consider on a large-scale all of the things it provides.

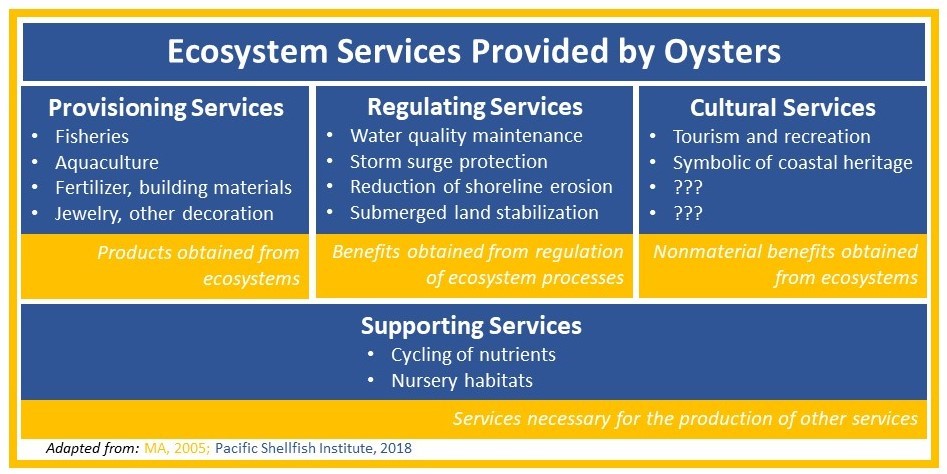

There are four categories of ecosystem service. Regulating services are the benefits received from regulation of ecosystem processes. One regulating service oysters provide is water quality maintenance. Provisioning services are the products obtained directly from ecosystems. This may be the one that you’re most familiar with — people eat oysters, and make money from the sale of oysters. Cultural services are the nonmaterial benefits obtained from ecosystems, and tend to be placed on the sidelines. Examples include tourism and recreation benefits. The fourth category, supporting services, are what’s necessary for the production of other services. For example, oyster reefs provide nursery habitats for other animals that in turn provide benefits to us. These categories are summarized in the figure included here.

As I began analyzing my interview data, especially when thinking about the “why or why not aquaculture” question, I started to look at the responses through this lens of ecosystem services. What was most interesting to me is the most commonly mentioned service type. People aren’t talking about the boatloads of money they might make, or how much they may need to spend to get started. They’re not talking about the pounds of nitrogen that one cage of oysters can capture, or the local water quality enhanced by their oysters.

Instead, they talk about how aquaculture gives them the opportunity to continue working on the water, or share a business with their children. It has a certain “feel-good” aspect that is appealing and is a welcome change from working behind a desk for some. On the other hand, for those not interested in aquaculture, it represents a different sort of independence when compared to public fisheries that some might view as constraining. These are just a few of the cultural service themes popping up in my interviews, but they suggest that this oft-ignored category of ecosystem services is important.

|

|

One recurring theme in interviews is that aquaculture enables watermen to continue working the water, enjoying time spent outdoors, albeit with a slightly different method of harvest. Credit: Adriane Michaelis. |

Thinking about the answer to my introductory question “Why/why not aquaculture” has inspired me to continue this inquiry in a more targeted fashion. Cultural services are poorly understood, especially when it comes to shellfish aquaculture. Yet, my data show that cultural services might be the most important thing to people considering a career in oyster aquaculture. Informed by the data collected within my Coastal Resilience and Sustainability Fellowship, I’ll pursue this research for my full dissertation.

Beginning this fall and supported by a National Science Foundation Doctoral Dissertation Research Improvement Grant as well as an Explorers Club Washington Group Exploration and Field Research Grant, I’ll work in Maryland, Virginia, Alabama, Florida, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island in order to describe the cultural services associated with oyster aquaculture. I’ll be working and talking with oyster farmers, commercial fishermen, and community members in all 6 states, to see just what the cultural services associated with aquaculture are and how they compare to cultural services associated with public fisheries. Can aquaculture match the social and cultural components of a public fishery? I’m hoping I’ll at least be closer to an answer.

Photo, top left: As aquaculture grows alongside public fisheries, it’s important to understand if it can match the social and cultural components of public fisheries. Credit: Adriane Michaelis

See all posts to the Fellowship Experiences blog