Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

Putting PFAS Regulations in Perspective

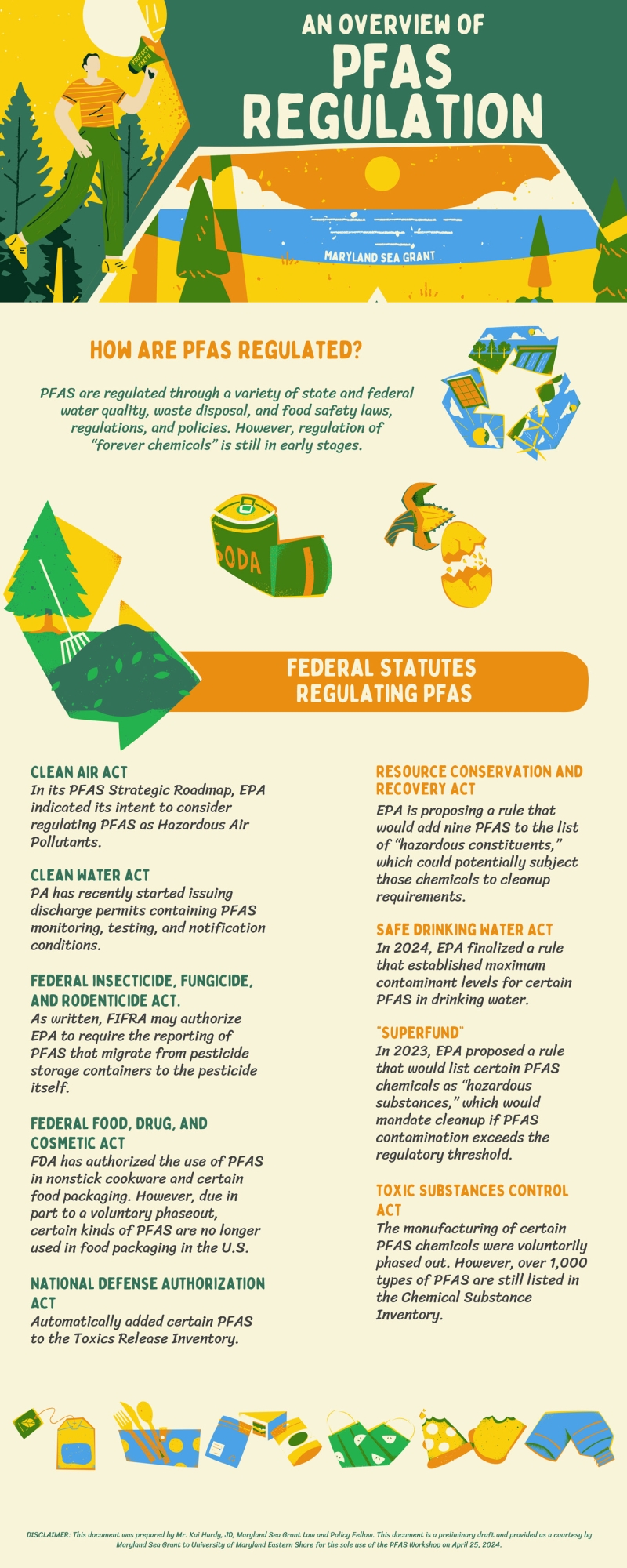

What in the world are PFAS? Potentially harmful, human-made chemicals found nearly everywhere. If they’re so harmful, are they regulated? Yes. How so? I’ll break it down.

One of my roles as a Sea Grant Legal Fellow is to help agencies, industries, and communities understand the laws and policies governing often complex scientific topics. PFAS are a prime example of scientific and regulatory complexity. The science aspect requires a high-level understanding of chemistry. The legal aspect requires a grasp of federal environmental and public health statutes, as well as a patchwork of state regulations. However, a PhD in chemistry and a law degree aren’t required to understand how governments are protecting us, our loved ones, our communities, and our environment from PFAS.

Health and environmental laws are often explained using highly technical language. This creates an access barrier, particularly for communities that are underserved, overburdened, or whose primary language is not English. My job is to provide accessible, digestible information on Maryland’s water-related issues (including PFAS) in plain terms. I’m grateful to have had the opportunity to do so for the University of Maryland Eastern Shore’s (UMES) PFAS Workshop earlier this year. But first, here’s a brief background on PFAS.

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are commonly known as “forever chemicals” because they persist in the environment long after release and are nearly impossible to destroy. They are found in air, water, soil, and the tissues of wildlife and humans. PFAS have water-resistant, oil-repelling, and stain-resistant properties. Because of these, manufacturers use them in rain jackets, nonstick cookware, stain-resistant carpets, and grease-resistant food packaging like microwave popcorn bags and pizza boxes. There are thousands of types of PFAS known to scientists, and new PFAS continue to be manufactured. The human health impacts, including cancer, of certain PFAS are well-documented.

Despite the harmful impacts of PFAS on human health and the environment, state and federal regulation of these “forever chemicals” is still in its early stages. Scientists are still learning about PFAS variants, their ability to bioaccumulate (increase in concentration in organisms over time), and the sources of their release into the environment.

UMES held a PFAS Workshop on April 25, 2024, to highlight the latest developments in the scientific and regulatory spaces. I was tasked with creating educational handouts for the workshop. The infographic and reference guide I developed help to explain the regulatory landscape of PFAS in Maryland and at the federal level.

Through my research, I found that Maryland has been a national leader in PFAS regulation. The state restricts the use of intentionally added PFAS in aqueous film forming foams (firefighting foams, also called AFFF), cosmetics, rugs and carpets, and certain types of food packaging. Additionally, the Maryland General Assembly passed a PFAS bill during the 2024 Legislative Session that requires the Maryland Department of the Environment to:

- Establish PFAS action levels for publicly owned treatment works (POTWs) and “significant industrial users”

- Collaborate with those POTWs and industrial users to develop PFAS mitigation plans

POTWs are essentially wastewater treatment facilities, owned and operated by state and local governments. These facilities treat and process sewage and industrial wastewater and discharge it into a waterbody. A “significant industrial user” is, according to the law, a private wastewater treatment plant that discharges an average of at least 25,000 gallons of wastewater per day.

Maryland’s strong PFAS laws reflect the state’s commitment to protecting its communities and natural resources—including the Chesapeake Bay and tidal wetlands—from PFAS contamination. Other states in the Bay watershed, including New York, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia, have also regulated PFAS in the environment. These efforts can help protect public health and restore and maintain water quality in the Bay.

Interested in learning more about PFAS? Read the latest issue of Maryland Sea Grant’s Chesapeake Quarterly magazine, which dives into the science, research, and policies surrounding PFAS in the Chesapeake Bay.

See all posts to the Fellowship Experiences blog