Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

Solving the Mystery of the Susquehanna Schmutz

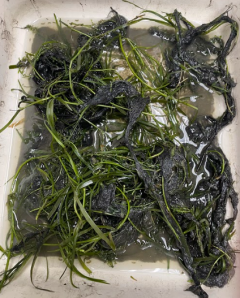

Last year, I wrote about “schmutz” at the mouth of the Susquehanna River. “Schmutz” refers to a stringy cyanobacteria, Lyngbya, that grows from the bottom of the Susquehanna Flats. Lyngbya is a stringy type of cyanobacteria that looks like a cross between algae and seaweed, but it can be toxic and irritating. Now, we know exactly what that “schmutz” is!

After months of attempting to extract the DNA from Lyngbya, and spending weeks organizing the DNA sequences, I confirmed that this “schmutz” is a type of Lyngbya that has been traditionally called Lyngbya wollei. However, as with many aspects of biology, as new information is gained, taxonomists have reclassified Lyngbya wollei as Microseira wollei. So now, we know the “schmutz” in the Susquehanna Flats should officially be called Microseira wollei. However, when conducting science experiments, new mysteries tend to appear, and we now have a new mystery on our hands: during our sampling, another cyanobacteria showed up that no one has documented to the species level—so our investigation continues.

This past summer, I collected many cyanobacteria samples from a large bed of submerged aquatic vegetation at the mouth of the Susquehanna River. Some cyanobacteria were thought to be the recently reclassified, Microseira wollei, and some were brand new—“schmutz” we have never seen before! My team and I collected all the samples we could and froze them immediately so I could preserve the DNA until I could extract it in the lab. Once we get the pure DNA from the samples, we can analyze the DNA sequences to identify the cyanobacteria we collected.

To extract DNA from the center of cyanobacterial cells, we first had to break down the cell walls. To do this, scientists use physical and chemical methods called extraction protocols. However, as we tried different extraction protocols, which can vary from organism to organism, we found that the cyanobacteria were hardier than we initially expected.

I spent months trying to break down the Microseira wollei and other cyanobacteria samples to no avail. It took many trials and many protocol changes until I finally found the secret ingredients to break down the cyanobacteria enough for a successful DNA extraction. By using a mortar and pestle to crush them and certain chemicals to break open the cells, I was able to successfully extract the DNA from the samples.

Once I extracted the DNA, I sent the samples off to Molecular Research DNA in Texas, where the company’s technicians sequenced different genes. I then organized this gene sequencing data to create readable sequences that I could try to match up to the ones recorded in the National Library of Medicine’s Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST), an online database that acts as an encyclopedia for DNA sequences. This is how we identified the cyanobacteria we suspected was Microseira/Lyngbya and confirmed its identity as the species of Microseira wollei.

We also sent in samples of the new mystery cyanobacteria, hoping to get another match. After running various sequences through the BLAST database, it was clear that this species has never been recorded. However, it is important to understand this species and record it for future reference so the science community can keep an eye out for where this cyanobacterium is popping up and how it may be impacting aquatic ecosystems.

This is where our story leaves off for now. This year, I will continue to extract more DNA from the samples collected this past summer and try to make sense of this new organism. Hopefully, by my next blog post, I will have a better understanding of this new organism, and maybe, it will be recorded in the BLAST database.

Top left image: Microseira wollei (dark green) covers the bay grass from the Susquehanna Flats. Photo: Shayna Keller

See all posts to the Fellowship Experiences blog