Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

Three Tips for Effective Communication for Non-native Speakers — and Everyone Else

Daytona Beach, 2011: I was at the biennial conference of a scientific society, the Coastal and Estuarine Research Federation. It was my first year in the United States and my first public talk in English. I remember standing on the stage, looking out at a room full of people; they all knew more about zooplankton and spoke better English than I did. Although I used to be a debate team captain and have won awards in speech contests — in Mandarin — I panicked and my brain went blank. I stumbled through my presentation so badly that even I didn’t understand what I was talking about.

English is not my native language, which I have found very daunting when speaking in front of a group of people. I would worry about not being able to express my thoughts clearly and embarrassing myself. Therefore, like many international students, I avoided public speaking. I tried hiding behind my computer and avoiding group activities, but eventually I didn’t feel like myself and decided to overcome this challenge.

Through diligently participating in various outreach events and giving many public talks, I found three tips especially helpful: love at first sight, the three-level storytelling method, and pictures express more.

1. Love at first sight

People absorb information better if they agree with it. To make intricate concepts understandable, I prefer to introduce complex ideas with simple and agreeable openings as appetizers. I call it the “love at first sight” technique.

For example, if I told a general audience, “I study the interactions between copepods, jellyfish, and fish under hypoxic conditions,” I think it would sound too complex and boring. Instead, I would start with, “I like rockfish,” which many people in Maryland can relate to.

This approach can be effective because psychologists have documented that under certain circumstances, once your audience agrees with your first sentence, it is more likely to agree with your second sentence.

Finding the magic first sentence for a particular audience takes research, so I have always tailor-made my message and have never given two identical talks. A well-customized message is not only about choosing the right words but also tailoring a message to the audience’s particular interests and tastes.

2. The three-level storytelling method

Once the audience understands the opening part of a speech, it is very tempting for the speaker to go into too much detail too soon. Many speakers at science conferences do this – and as a result, they can lose their audiences. I found myself often getting lost after hearing only one-third of a presentation and I would just log off; likewise, I noticed sometimes only people in my field could follow my talk.

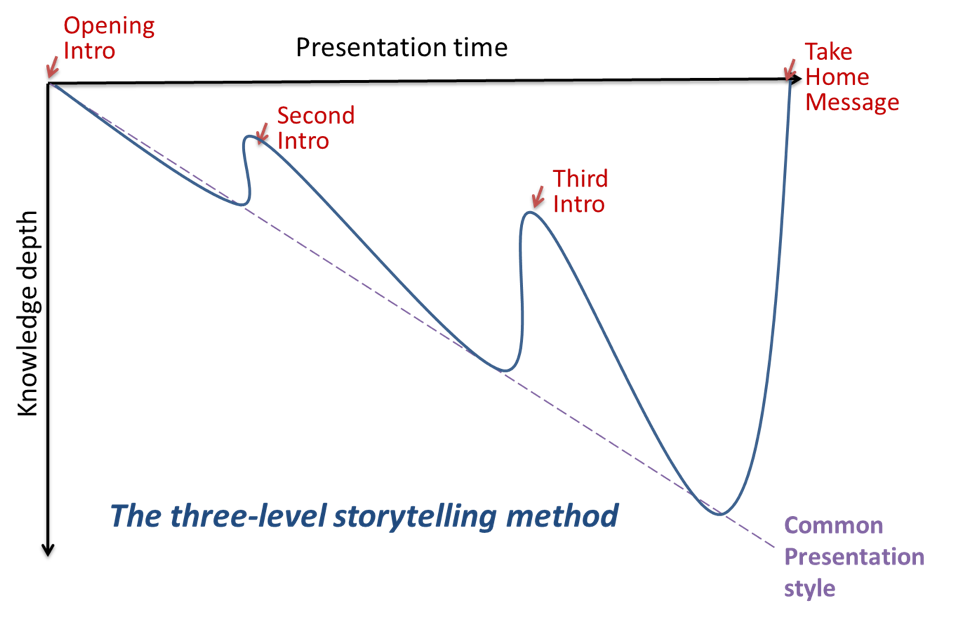

Instead, I found it is more effective if I break the message into three parts and prepare a simple introduction for each. With this technique, even if the audience does not understand some of the information or they have lost track somewhere, they could pick up the thread again from the intro to the next section of my talk. Once, after I used this technique in my student seminar, a physics post-doc told me that my presentation was the first biology talk she was able to follow and understand completely.

Most important, always conclude a discussion of complexity by providing simple take-home messages or summaries. People usually remember your beginning and ending the best. If your audience understands the opening and the closing of the speech, chances are they will comprehend the message you were trying to communicate.

Three-level storytelling method. Figure credit: Katherine Slater

3. Pictures express more

A good picture can say a thousand words, and it is an advantage that every non-native speaker should take. Besides relying on figures to illustrate my points, I further adopt Coco Chanel’s famous mantra about decorating: “Take at least one thing off.” After designing a figure, I step back and then see what I can remove, repeatedly, until the chart expresses only the most essential information.

By showing a picture first, it gives audiences a sense of what is coming up next, and my explanation is then just an echo of the picture and thus significantly decreases my language burden.

The academic world tends to be little on visual design and considers it is superficial, but graphic design is a desirable skill not only in science communication but also in budget review and proposal speeches. During an internship I held at the Environmental Protection Agency, I developed my skill at using Adobe Illustrator, which became very handy and useful to scientists and managers. The art skill created a niche for me, and it got me an opportunity to work on the EPA’s annual budget review prepared for Congress. I feel fortunate that I got opportunities to hone graphic skills in graduate school.

Conclusion: communicating beyond words

Studies indicate that 93 percent of communication is nonverbal, like gesture and tone, and only 7 percent comes from words. Being unable to use my first language forces me to focus on the 93 percent that I used to overlook. I regard this statistic as a hidden blessing.

Love at first sight, the three-level storytelling method, and pictures express more: these three tips reduce my fear of speaking in public in English and increase my confidence. These tips are universal and are beneficial to both non-native and native speakers.

Photo, top left: In this presentation, I describe my research on interactions between jellyfish and the food web in the Chesapeake Bay under low oxygen conditions. Credit: Katherine Slater

See all posts to the Fellowship Experiences blog