Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

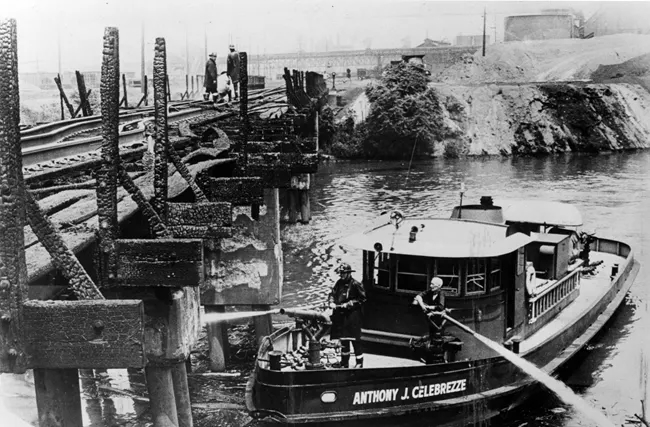

The Train that Sparked the Clean Water Act

On June 22, 1969, a train chugged along a bridge over the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland. This was a common sight at the time, but little did onlookers know, this train would result in one of the most important environmental regulations in the United States.

In the 1960s, the Cuyahoga was not a picture of health. Located in the heart of America’s industrial region known as the “Rust Belt,” the Cuyahoga was one of the most polluted rivers. In the US in the early-to-mid twentieth century, it was regularly saturated with oil and toxic substances, and many parts of the river near Cleveland contained hardly any fish or plants.

At the time, one observer described the Cuyahoga as a river that “oozes rather than flows” where a person “does not drown but decays.” So when the train released a spark that landed in its waters, the Cuyahoga immediately burst into flames. As appalling as the 1969 Cuyahoga Fire was, it should not have been surprising. The river had caught on fire a total of 13 times, according to some estimates.

The Cuyahoga Fire was one of several so-called natural disasters that contributed to the environmental movement of the 1970s and prompted federal regulation of the nation’s waters. In 1972, Congress enacted the Federal Water Pollution Control Act, better known as the Clean Water Act, which prohibited the discharge of pollutants into US waterways from a point source without first obtaining a permit from the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The Clean Water Act also prohibited the discharge of dredged and fill material into US waters without a permit from the US Army Corps of Engineers.

For nearly four decades, the Supreme Court interpreted the Clean Water Act to include wetlands adjacent to major rivers and lakes in its protection. This led to the restoration of many waterways, including the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries and tidal wetlands. This all changed in 2023 in the landmark case Sackett v. EPA, in which the Supreme Court ruled that wetlands are not covered under the act unless they have a “continuous surface connection” to “relatively permanent bodies of water” like an ocean, lake, or major river, and are “indistinguishable” from those waters. Essentially, this blockbuster court decision punted wetland regulation responsibilities to the states.

Approximately 60% of Maryland’s wetlands lost Clean Water Act coverage due to Sackett. However, there’s good news: Maryland has strong wetlands laws, so most wetlands in Maryland are protected under state law and are subject to permitting requirements. Despite its comprehensive program, there are still gaps in wetland protection created by the Sackett decision that the State seeks to fill. As part of my Maryland State Law and Policy Fellowship, I am writing a law review article exploring the legal and policy gaps in Maryland’s wetlands program and identifying the tools the State could use to further protect its wetlands.

In June, I attended a conference that convened legal, policy, and science experts to discuss the Sackett decision’s implications. Specifically, we discussed how the US will proceed in its regulation and protection of wetlands. Conference panels covered the future of litigation, tools, and other strategies for determining whether wetlands are covered under the Clean Water Act. We also discussed alternative approaches to federal regulation, including state regulation, private governance, and incentive-based approaches. The conference allowed me to network with experts and learn the creative ways in which other states are responding to the Sackett decision.

It was only fitting that the conference was held in Cleveland, the home of the once unswimmable, undrinkable, and uninhabitable Cuyahoga River, and, arguably, the birthplace of the environmental movement. Research shows the Clean Water Act has been enormously successful in “restor[ing] and maintain[ing] the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the Nation’s waters.” It also eventually led to the establishment of multi-jurisdictional water quality agreements such as Chesapeake Bay Program.

However, the Sackett decision jeopardized the effectiveness of the Clean Water Act in protecting wetlands, which are a vital resource in Maryland and other coastal states. The goal of my article is to inform Marylanders of the legal gaps left by the Sackett decision and inform decision-making with respect to the state’s wetlands laws.

Top left photo: Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge in winter. Photo: Nicole Lehming

See all posts to the Fellowship Experiences blog