Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

American Eels: Population, fishery, and poaching

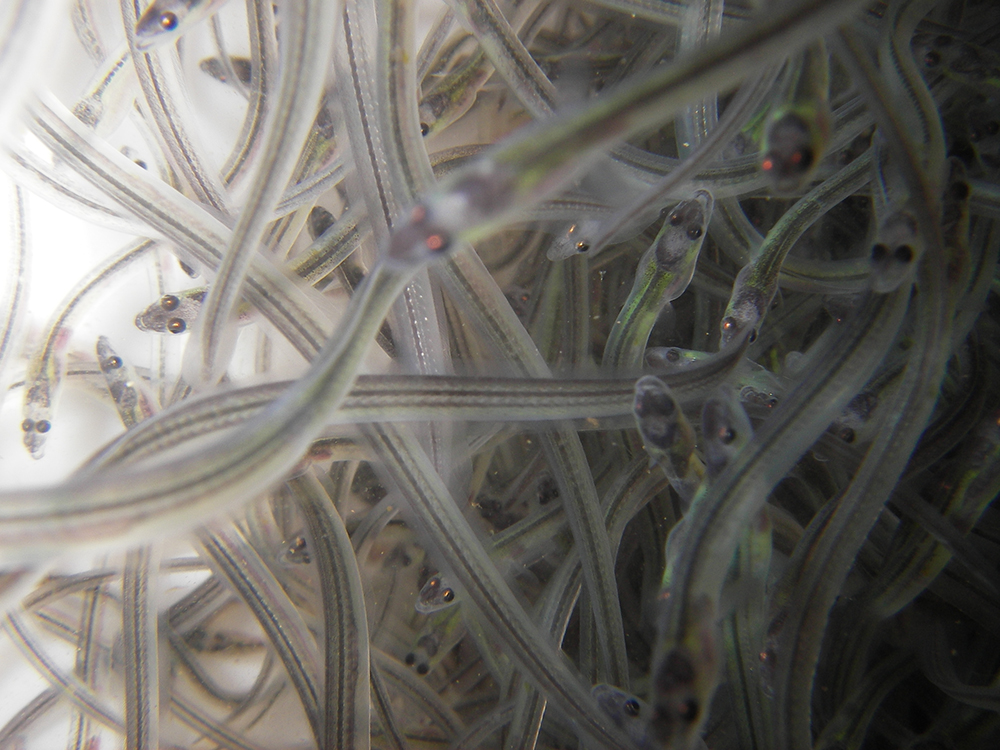

Thousands of American eels captured at the Conowingo Dam eel ramp are swimming en masse in a huge holding tank, waiting to be trucked upstream where they will be released to restock part of the Susquehanna River and its tributaries. As a species that has existed for over two million years and can be found in diverse habitats worldwide, eels’ abundance seems unassailable, but the thousands in this tank tell a different story.

Since the Conowingo Dam was built in 1928, eels have lost access to some 400 miles of riverine habitat, decimating a once vibrant eel fishery and altering the river’s ecosystem. When eels are restocked above the dam, they still risk death on their downstream spawning migration as they pass through the dam’s turbines. The Conowingo is just one of several dams on this river affecting eels’ habitat, and it’s just one example of threats to eels’ survival in the Chesapeake Bay and elsewhere.

The Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC), manages the eel fishery for the Atlantic coast states. Its 2017 stock assessment update for the American eel, formally known as Anguilla rostrata, notes that in 1979, fishermen coast-wide landed 3.67 million pounds of eels. These are typically yellow eels, a sexually immature mid-life stage that the eels are in for up to 20 years before their final maturation stage. Since then, landings—which is one way to measure abundance—have dropped steadily, down to about 700,000 in 2002, making the eels’ status “depleted.”

“While results varied among individual abundance indices and analyses, the 40‐year‐plus trend of yellow eels showed large declines in abundance during the 1980s through the early 1990s, with primarily neutral or stable abundance from the mid‐1990s through 2016,” the report says, though it also acknowledges, “Despite the large number of surveys and studies available for use in this assessment, the American eel stock is still considered data‐poor because very few surveys target eels and collect information on length, age, and sex of the animals caught.”

In Maryland, the story is a little better. It is one of the only states that conducts a fishery-independent assessment of yellow eels—an eel pot survey on the Sassafras River that ran from 1998-2000 and was reinitiated in 2006, says Keith Whiteford, a fisheries biologist with the Maryland Department of Natural Resources. That survey has shown a positive trend in abundance since 2006. Likewise, the commercial eel pot catch per unit effort (CPUE)—a standard measure of abundance—in Maryland has also trended upward since 2003, he says.

“Maryland has averaged a harvest of approximately 550,000–560,000 pounds annually for the last 10 years, and this comprises approximately 60 percent of the coastwide eel harvest,” Whiteford says. “While our harvest has been significant relative to the whole coast, our populations here have shown not only stability but indicators of increased abundance."

Still, he says, “There are definitely localized areas up and down the coast that have experienced significant declines, and despite some of these areas showing some stability over the last 10 years, overall populations in these areas are at a small fraction of what they were in the 70s and early 80s.”

In all states the poaching of glass eels, a juvenile life stage in which the eels are only two to three inches long with the fins and bodies of adults but the translucence of larvae, remains a concern. The ASMFC permits only Maine and South Carolina to conduct a limited harvest of glass eels, but the money in the lucrative fishery—driven by an Asian demand for eels that are grown in aquaculture until large enough to become sushi—has supported a thriving black market. In 2019, the legal market price in Maine for glass eels reached $3,000 per pound. Ten years earlier it was $100 per pound.

A three-year undercover investigation led by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) called Operation Broken Glass, which wrapped up in 2014, led to more than 20 people up and down the East Coast being indicted for large-scale poaching of glass eels. Maryland was one of the states that did not have a conviction, Whiteford says.

Part of the demand for glass eels landed on American eels once the European Union banned export of European eels in 2010, after the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) had placed European eels under protection in 2007. The USFWS has considered Endangered Species Act protection for the American eel in 2007 and 2015, but in both cases found it unwarranted.

This is Part 2 of a series. Learn more:

Part 1: American Eels: Population, fishery, and poaching

Part 3: American Eels: Dams, habitat loss, and restocking

Part 4: American Eels and Mussels: An essential relationship

See all posts from the On the Bay blog