Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

The Maryland Sea Grant Bookstore will be closed for the winter holidays from Monday, December 15th to Friday, January 2nd and will not be taking orders during that time.

A Ballooning Effort: Maryland bans intentional balloon releases & new campaign offers information about impacts

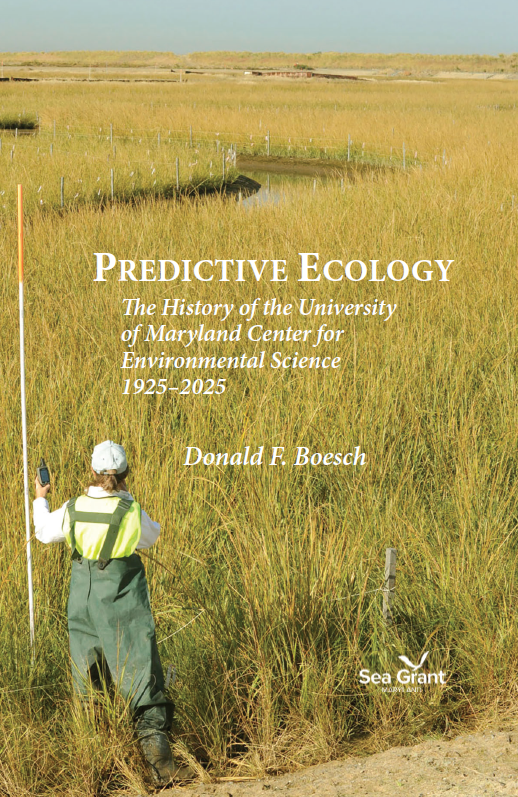

Thick clouds are brooding on an early October day at Assateague Island on Maryland’s Atlantic coast, but no one in the crew of Maryland Conservation Corps members is paying much attention to the sky; their focus, instead, is on what has fallen out of it.

Methodically and carefully, eyes cast toward the sand underfoot, they are surveying a measured mile of the beach. They’ll pick up any trash, from face masks and plastic tampon applicators to plastic cigarette filters and the ubiquitous water bottles. But their main quarry today is balloons and their remnants—bits of ribbon, clips, and half-melted latex that resembles a wad of gum, grubby plastic bags in the shape of a star or heart, the foil that once brightened them or sent a message—“Happy Birthday!” or “Congratulations Graduate!”—long gone.

Three of the crew serve as recorders. Every time a balloon or remnant is found, they record its identifying information on a data sheet and note the precise position using a hand-held GPS. They’re using a survey protocol—“Balloon Litter Monitoring and Assessment for the Coastal Environment”—developed under a NOAA grant and finalized in 2018 by Clean Virginia Waterways of Longwood University and the Virginia Coastal Zone Management Program.

They’re led by Maryland Conservation Corps (MCC) Crew Leader Erin Swale and Donna Morrow, program manager of Maryland Department of Natural Resources’ (DNR) Chesapeake and Coastal Service and a member of the Mid-Atlantic Regional Council on the Ocean’s (MARCO) Marine Debris Work Group. The MCC is an AmeriCorps service program that is managed by the Maryland Park Service and engages young adults in natural resource management and park conservation projects throughout the state.

Today’s beach survey is one of two annually at this location. It’s part of the MARCO Marine Debris Work Group’s plan to track the abundance, distribution, accumulation, and fate of balloons and their associated litter on Mid-Atlantic beaches. Volunteers and staff in each member state—New York, New Jersey, Delaware, Virginia, and Maryland—conduct similar surveys.

This one is particularly significant because on Oct. 1, 2021, Maryland joined its neighboring states of Virginia, Delaware, and New Jersey in banning intentional balloon releases. Some Maryland municipalities, including Baltimore and Ocean City, as well as Queen Anne’s County, already had similar laws on their books. But a statewide law, specifically barring anyone 13 and older from intentionally releasing more than 10 balloons, passed during the 2021 General Assembly.

“In Maryland it’s now illegal to be a plastic balloon litterbug and that’s good news for our land, water, and wildlife,” Maryland Department of the Environment Secretary Ben Grumbles said in a media release. “With the rising tide of plastic pollution, this new law is an important and timely step for the health of our Chesapeake Bay, coast, and ocean.”

The timing is also significant because the National Aquarium in Baltimore, along with the New York Aquarium in Brooklyn and the Virginia Aquarium in Virginia Beach, partnered with MARCO to launch the Prevent Balloon Litter campaign in October. Funded by a NOAA Marine Debris Program grant, the broad new campaign aims to raise public awareness about balloon litter and provide people with other ways to mark significant events.

“This community-based social marketing campaign gets at the heart of changing behavior and influencing people in the Mid-Atlantic area to say no to balloon releases,” Morrow says. “Whether they would organize an event or just be invited to participate in a balloon release, we are offering education about the impacts of balloon litter, demonstrating alternatives, and encouraging people to sign a pledge not to release balloons.”

Balloons pose a particular threat to birds and marine animals through entanglement and when they are mistaken for food and ingested (a plastic balloon looks remarkably like a jellyfish—a top food item among sea turtles—when floating). Although it is hard to quantify how many animals are killed or hurt by balloon litter, the NOAA Marine Debris Program website cites a 2016 report that “when marine debris experts were asked to estimate which common litter items posed the greatest entanglement and ingestion risk to seabirds, sea turtles and marine mammals, balloons were ranked third after fishing gear and plastic bags/utensils.”

According to MARCO, between 2016 and 2019, more than 29,800 balloons were found on Mid-Atlantic beaches during International Coastal Cleanup events. A five-year monitoring project on three remote Virginia beaches found 11,441 balloons and related pieces, making balloons the top marine debris item, surpassing even plastic water bottles.

NOAA also points out that balloons are a unique form of pollution because many people buy them with the specific intent to release them into the air. They’re sent up to commemorate the death of loved ones or to celebrate marriages, among other events. Just two weeks before the October 1 law took effect in Maryland, groups including the Ocean City Chapter of the Surfrider Foundation and the Assateague Coastal Trust urged the National Alumni Association of the University of Maryland Eastern Shore to cancel a balloon release scheduled as part of a day of remembrance (the association moved the release off campus).

The new Prevent Balloon Litter campaign builds on work by Clean Virginia Waterways and the Virginia Coastal Zone Management Program, who in 2018 conducted a social marketing study to understand more about why people release balloons and how to motivate them to make a different choice. Among their findings, they learned that many people didn’t realize that balloons fall back to earth, or they believed that latex balloons would harmlessly biodegrade (research is continuing into the fate of latex balloons; plastic ribbon attached to such balloons does not biodegrade). Another finding was that balloons are mostly released at parks, schools, wedding venues, and churches; more recent research added home parties to that list.

The campaign’s website provides public education about the reasons behind this type of littering, the dangers it poses to the environment, a pledge that people can sign to never participate in a balloon release, and an array of alternative ways to mark significant events—among them blowing bubbles, distributing packets of native plant seeds, planting a tree, offering celebrants ribbon wands, paper airplanes, or pinwheels, or doing an indoor drop of non-helium-filled balloons.

“We understand the gratification people get from watching balloons go up and out of site, but we have to remember that all balloons come back down somewhere,” Morrow says. “This new law reflects that fact, and our outreach campaign simply asks people to switch to one of the many tributes and celebrations that do not harm animals or our environment.”

Photo, top left: MCC Crew Leader Erin Swale (right) works with MCC member Derek Cross to record the location and details of a foil “Happy Birthday” balloon found on a dune on Assateague Island. Photo credit: Wendy Mitman Clarke / MDSG

See all posts from the On the Bay blog