Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

Behind the Scenes: Getting the shot takes teamwork

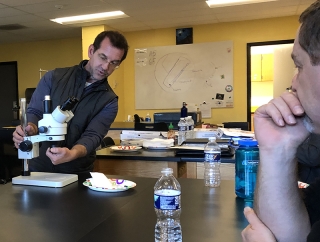

Making the invisible visible is an important, yet challenging, part of sharing science. It’s one our communications team recently took on with Assistant Director for Education J. Adam Frederick to determine the best method for capturing images of microplastics in a laboratory setting at the Institute of Marine and Environmental Technology (IMET) in Baltimore, Maryland.

Frederick is working with educators and researchers to examine and document the presence of microplastics, or tiny fragments of plastic, in aquatic ecosystems. The work stems from his Biofilms and Biodiversity curriculum, which engages students in project-based learning through the collection and observation of biofilm communities on discs submerged in the Baltimore Inner Harbor and in international waters including Sweden, Germany, and Spain.

These communities are now being examined for microplastics as well, and Frederick is testing new methods for classrooms to examine and catalog the particles. Our communications staff spent a day with him at IMET to test several different approaches for photographing samples.

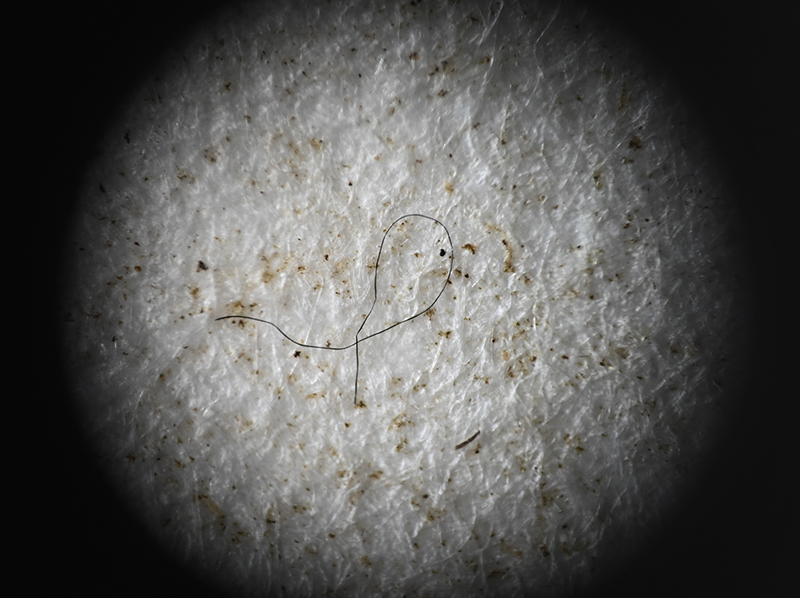

Our team tested several approaches, including extreme macro photography, using an objective lens mounted directly on a digital camera, as well as connecting the camera to two different types of microscopes. One was an inverted compound microscope with objectives mounted under the stage instead of above, which allows for a larger sample to be placed on the scope instead of just a slide. The other was a stereo, or dissecting, microscope, which allowed the capability of lighting with reflected lighting. That provided a more three-dimensional image that defines the material’s texture and color in a truer form.

We placed samples in a glass Petri dish for viewing on the inverted compound microscope and then varied the objective from 4x to 20x magnification with transmitted light. It provided good depth of field and color reproduction, and overall is an excellent scope for the classroom to look at communities of biofilms, cells, protists, and hemocytes from oysters.

For the stereomicroscope, we used a 2x Barlow lens for macro work. Frederick feels that these scopes are the best choice to view other aspects of his biofilms and biodiversity work at IMET, as well as capturing images of the anatomy of organisms like oysters.

So what do microplastics look like under a scope? Here are a few of the resulting images captured by Frederick and Nicole Lehming, our graphic designer and producer. Overall, the team was happy with the results of their first round of testing, and Frederick will share details of the most successful techniques with the teachers who will be incorporating microplastics into their Biofilms and Biodiversity curriculum.

Photo, top left: J. Adam Frederick reviews microscopic techniques with teachers at South Carroll High School. Credit: Wendy Mitman Clarke / MDSG

Macro photos taken by Nicole Lehming and J. Adam Frederick / MDSG.

See all posts from the On the Bay blog

.jpg)