Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

A Host with the Most: Raising Maryland’s spotted salamander larvae, students study a unique example of symbiosis

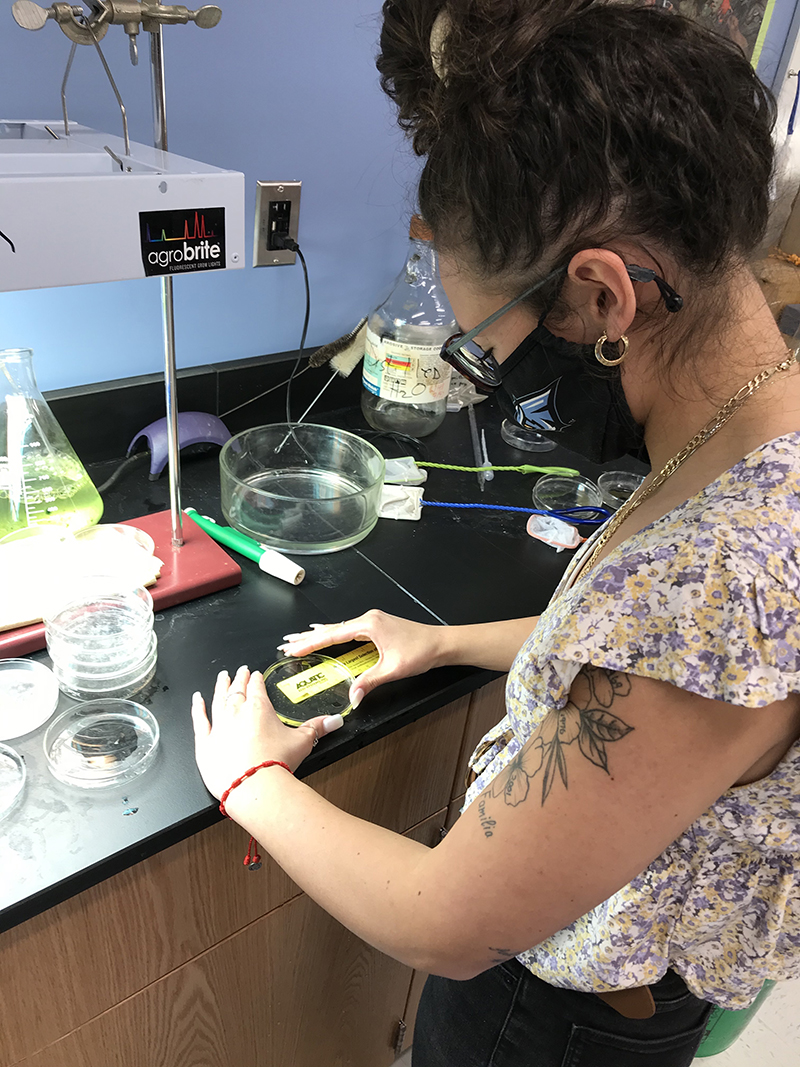

“Ah, man. I lost him.” Carter Ruby, a junior at Westminster High School, sighs and reaches into the 10-gallon aquarium tank again, a petri dish gripped carefully in his fingers. Beside him, junior Bella Diaz laughs and bends over her own petri dish, this one placed precisely on gridded paper. She snaps an image with her phone and then pours the dish’s contents into a large glass bowl on the counter beside her.

“Oh my gosh!” Ruby yelps. “I just got four! So, I figured out the method. Put it in, push it down, and it sucks them in.” He lifts the dripping dish from the tank and hands it to Diaz, who sets it on the paper and positions it to shoot another photo; the images will be stored for subsequent data collection.

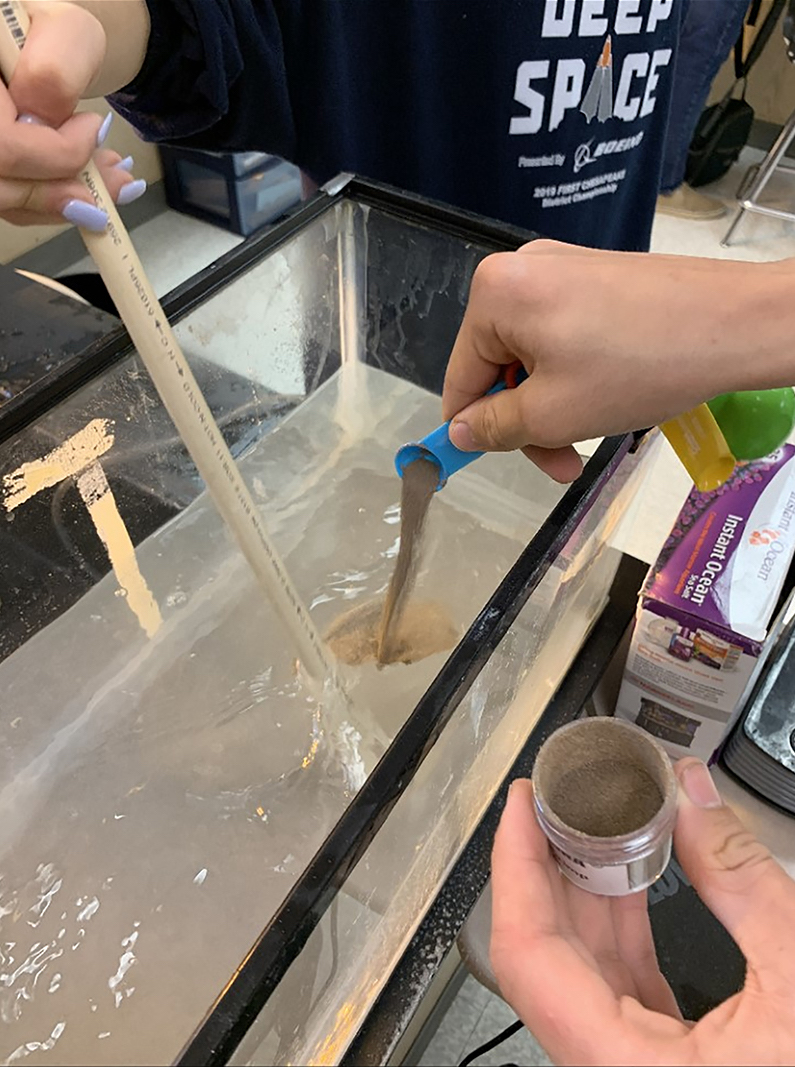

It’s a peculiar form of fishing, to be sure, but then, the quarry is also out of the ordinary; weeks-old spotted salamander larvae (Ambystoma maculatum) that Ruby, Diaz, and other students in this section of the school’s Science Research course are raising from egg masses gathered at a nearby vernal pool. With their Maryland Department of Natural Resources (DNR) special permit, the students are able to hatch, feed, measure, and study the larvae for 30 days before they must be returned to the pool where J. Adam Frederick, Maryland Sea Grant’s assistant director for education, and Jim Peters, secondary science supervisor for Carroll County Public Schools, collected them.

“The protocol is very specific,” Peters says, noting that the larvae must be released within three meters of where they were collected. “We have to be careful and understand the sensitive nature of that amphibian.”

This is the sixth spring that six Carroll County high schools and about 100 students have collaborated with Frederick and DNR’s Wildlife and Heritage Service to participate in this highly hands-on science with a Maryland critter that may seem ordinary but in fact may be unique in the world. In a singular example of symbiosis, spotted salamanders are the only vertebrate known that lives with another organism—in this case a plant—growing inside its cells. The alga Oophila amblystomatis is found nowhere in the world but inside the spotted salamander embryo. It uses the embryo as a host, absorbing nitrogen and carbon dioxide expelled by the growing salamander, while the salamander benefits from oxygen and sugar produced during the algae’s photosynthesis.

Students are able to see this symbiosis in the embryo’s greenish tinge that develops as the egg masses mature.

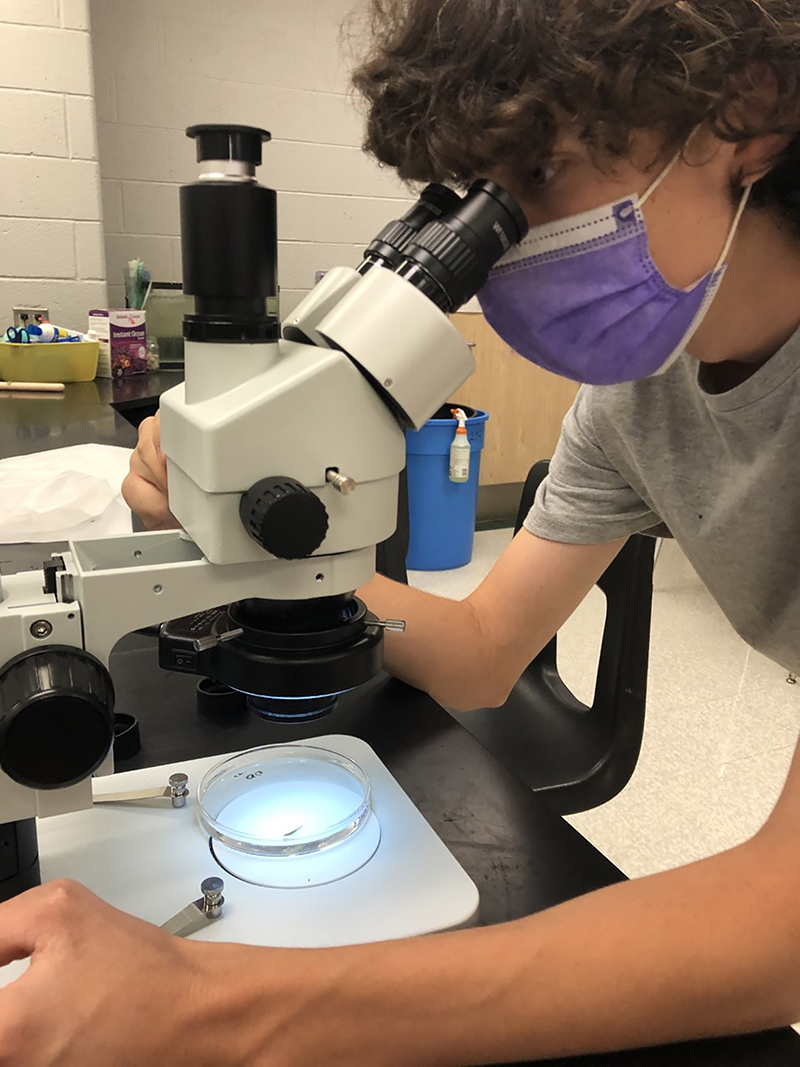

“We can set them up under natural light, and we can encourage the algae even more with artificial light. We can also block light to produce a lower-light group,” says Don Adams, the Westminster High School biology teacher who’s helping guide Ruby in his research project this spring. “We measure growth and survival. We try to estimate how many eggs are in each mass, and based on that we will try to estimate hatching percentage. The main variable we’re looking at is, does the algae actually show a measurable benefit? We use the light to encourage the algae, which maximizes the benefits the algae produce: sugar and oxygen.”

Spotted salamanders are Maryland natives, though they range as far north as Nova Scotia and down to Texas. Living in swamplands and deciduous forest, they spend most of their time under leaf litter and logs and even underground in tunnels and burrows of small mammals. They use their sticky tongues to rummage the forest floor for a variety of prey from snails and centipedes to earthworms and slugs.

Early each year, just after the snow has thawed, the chilly spring rains trigger a massive migration (see video, below). Under the cover of darkness, the salamanders emerge from their terrestrial enclaves and make their way to the same vernal pool where they were hatched. Here, they dive in by the hundreds and writhe and twist in a reproductive tangle. The egg masses that result look like subaquatic cotton balls.

Up to 90 percent of their larvae can be consumed by pool predators even before they hatch (they may even eat each other as larvae). If they survive to adulthood, they can live up to 30 years.

Their unique symbiosis with Oophila amblystomatis has only recently been discovered and studied; Frederick, who’s long been fascinated by their annual migration, says that as soon as he learned about it, he realized the salamanders presented an ideal way to study the concept.

“What are all the usual symbiosis examples you see in a standard tenth-grade text? Sea anemone and clown fish, lichen, coral,” he says. “But this is the example of symbiosis that should be used as a case study for teaching, because it’s the only vertebrate animal to have a symbiotic alga that we have found so far.”

That it’s practically in these students’ backyard only makes it an even more powerful teaching tool. Andrew Gibson, a teacher at Century High School, says the intensely hands-on aspect of being responsible for “a relatively large population of vulnerable individuals” also captures students’ excitement.

“Every student is involved to some extent, even if it’s just learning that this is an exceptional salamander,” he says. “But it’s usually a small group, four or so, who are working fulltime to make sure they are healthy. That’s their everything, making sure as many of these little guys live as possible.”

As they work side-by-side to capture, measure, and photograph the larvae, Diaz and Ruby comment periodically on unusual features or behavior they see in their tiny charges.

“They grow pretty fast,” Diaz says. “We’ve noticed that their heads grow a lot faster than their bodies.”

“One thing we’ve noticed in the biggest one we have [about 9 cm], they’re almost see-through, so you can see into the body,” Ruby says.

Peters, who each spring pulls on his hip waders to move gently through the pools and gather egg masses, then later to return the young salamanders, says the students working with the animals can’t help but wonder “how in the world did that ever happen, that algae and a salamander have become dependent on one another?”

“A lot of times, kids, their lives move really fast, and it’s neat for them to be able to step back and say, ‘Wait—that cool thing is living pretty close to me?’ And the answer is yes,” Peters says. “But we don’t know a lot about them, so you can be part of discovering more things about them.”

Photo, top left: In this photo illustration, spotted salamander embryos in egg cases are surrounded by the symbiotic alga Oophila amblystomatis. Photo illustration credit: J. Adam Frederick/MDSG

See all posts from the On the Bay blog