Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

Hybrid Science: Virtual learning during COVID-19 opens a window to enhanced science education

The coronavirus pandemic has forced schools worldwide to close and shift their classes to online learning—a prodigious undertaking for teachers and students that has thrown traditional education for a violent loop. But some educators, among them J. Adam Frederick, Maryland Sea Grant’s assistant director for education, believe this moment of disruption is an opportunity to change the way schools are delivering science education to their students.

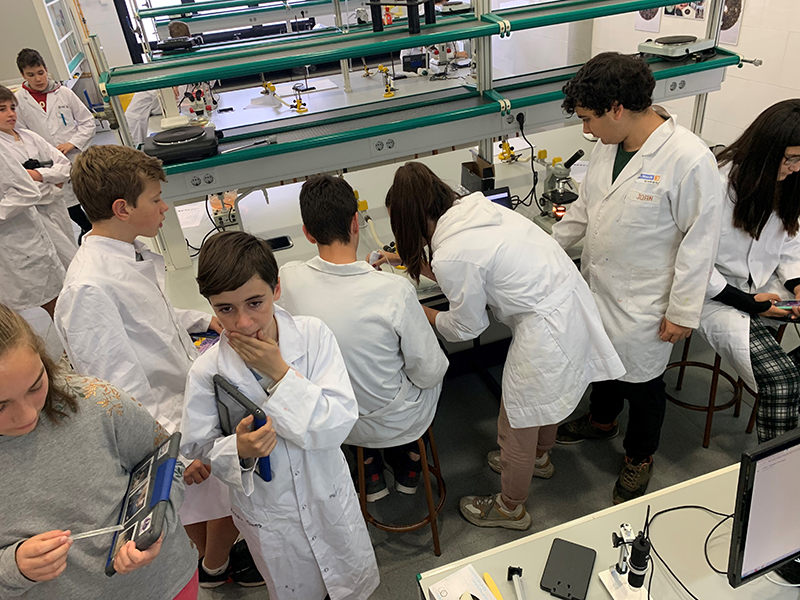

Frederick and his collaborators have quickly created a global classroom from an existing project-based learning model called VIRTUE-s, which has been an international research and education platform since 1997, supported in part by Maryland Sea Grant. The new iteration, called VIRTUE-s OCEAN, is enabling a hybrid of formal educators (the students’ classroom teachers) and informal educators (people like Frederick as well as other experts in pertinent fields) to meet students online to help them advance their studies in marine biodiversity.

For six Mondays this spring some 75 high school students from three schools in Sweden, Germany, and Spain, as well as 12 teachers and about a dozen informal educators and researchers, met online for an hour-long class. Since all of the students are multilingual, the classes are in English.

The class was held via a video conferencing platform called Zoom at 6:30 a.m. on the U.S. East Coast—12:30 p.m. in western Europe. For the first 20 minutes, the day’s expert would lecture on the theme, including ocean literacy, ecology, biodiversity, and using video to present research. Then the students would break out into small groups within Zoom to spend the next 20 minutes working on a task related to the theme. For the last 20 minutes, the whole class would reassemble, review their work, then outline the project they would work on offline with their group to bring to the following week’s class.

Dennis Augustsson, a PhD candidate at University West in Trollhättan, Sweden, led the first week’s session on video production of scientific research. He asked students to come up with three challenges to presenting their biodiversity research in a short film or video. After a bit of joking in Zoom’s chat box about someone’s pet bird making noise, the students got down to work in their groups and came back with insightful questions for Augustsson to address. They included: How do you change your presentation based on the audience; how do you speak to keep the audience interested; what’s the best editing software; how do you balance voice-over and text; and what form or genre is the best way to present scientific information?

To help teachers integrate the VIRTUE-s OCEAN classwork into their own classrooms and curricular demands, the teachers themselves chose the topics for the classes. They could also choose which aspects of the topics best fit their students’ and schools’ requirements. Guest lecturers like Augustsson and Frederick developed course materials and posted them on the VIRTUE-s OCEAN website ahead of each class for students to access and review. Each class was also recorded and published on the site if a student or teacher needed to revisit it.

The project is funded by the European Union-based program called Erasmus+ that supports science, education, and training for students and organizations.

“It’s an interesting experiment,” Frederick says. “We tried to make it much more interactive than a traditional MOOC (massive open online course) when people are just sitting and watching.”

Frederick has been impressed with how nimble the European teachers and school systems have been to help develop the new course and integrate it into their traditional classrooms. The class’s hybrid nature—merging formal with informal education—also serves as a model for reimagining how science education is presented in American schools, he says. Rather than restricting science learning to a rigid formal curriculum, why not leverage the expanse of information and research being created by institutions such as the Smithsonian, National Geographic, and the Sea Grant College Program and enable teachers to use them in the digital space while integrating them with their traditional curricula?

The VIRTUE-s OCEAN project is “a combination of both formal, because we’re working with teachers and students directly influencing their curricula and how they deliver the materials, and informal because a lot of the partners are from informal institutions, but they are delivering the information to students in concert with their teacher and school and using it as part of their online environment,” Frederick says. “It’s a clear, well-defined partnership with the schools that are making changes to the way they deliver science education.”

See all posts from the On the Bay blog