Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

Prepping for Peeler Crabs

Crabbers in Maryland usually start working weeks before the blue crabs start moving out of the mud where they overwinter. That’s especially true for the handful of watermen who set up bank traps designed to catch peelers, hard crabs that are getting ready to molt, to shed their shells and morph, for a brief period, into soft crabs.

For John Barnette this year’s crabbing season began last fall when he left stacks of poles sticking up in 30 different spots along the marshlands that line the south side of the lower Wicomico River.

This April he began hauling those poles out of the marsh and planting them in the shallows along the river. As he worked he had to pick his way among old tree stumps hidden underwater along river bottom that was once hard land before sea level rise and erosion pushed back the shoreline.

There's a lot grunt work in his peeler prep. He had to drive each pole deep enough to withstand winds and storm waves for the next seven months.

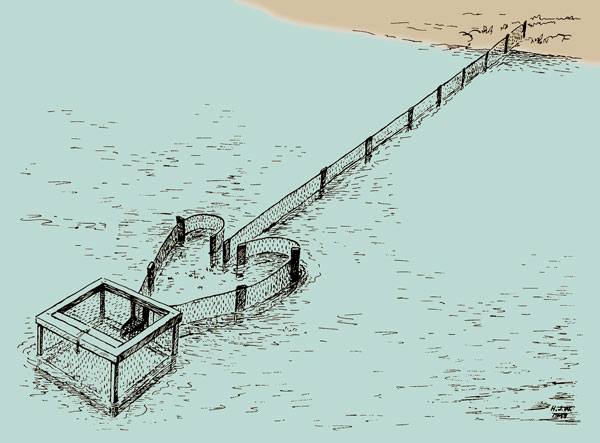

Between the poles Barnette installed wire panels, tying each one in place and creating a flow-through barrier. The technique, he said, is similar to the fishing weirs once used along this river by Native Americans of the Wicomico chiefdom.

As the poles and panels reach out from the shore, they create “the leader” for the bank trap. It's an aptly named structure. As blue crabs get ready to molt, they seek shelter along the shore, only to run into the wire panels which “lead” them away from the shore.

At the end of the “leader,” peeler crabs will find themselves entering a structure called the “heart.”

To hold his "heart" in place, Barnette has to sink a pole at each corner.

To ease the grunt work he has some technology Native Americans never had. A motor-driven water pump helps him blast holes deep enough to anchor his poles in the river bottom.

The bank trapper was now prepped for the peeler runs of May, and they are often the largest of the season. Each of his almost-complete bank traps requires 15 poles, a lot of “leader” panels and a sturdy “heart.” In this long afternoon he managed to set up four of these bank trap structures, the last of the 30 bank traps he will work this season.

Bank traps are sometimes called "peeler pounds" because their design resembles traditional pound nets used for catching finfish. After the "leader" and the "heart" comes the trap itself, a wire cage standing four feet wide and five feet high, tall enough to keep the top out of the water at mean high tide and give breathing room to any turtles that might wander in. That doesn't happen with Barnette's traps, thanks to a TED, a turtle exclusion device he uses. He keeps turtles out so they won't eat his crabs before he unloads them.

Fish often show up in Barnettes' traps, making them a popular hang out for herons and ospreys and eagles. They wait patiently for Barnette to show up and empty his traps of crabs and flip them any fish he may find there. "I'm like the mailman," he says. "I make the same stops, the same place everyday."

Bank trappers like Barnette are a dwindling tribe. They follow a form of crab catching not found any more along more populated rivers where homeowners prefer their water views empty of any old-time fishing gear. Bank trapping is currently allowed only in Somerset County, one of the least populated counties in Maryland, and along part of Eastern Neck Island, a sanctuary for migratory birds.

The payoff to all his prep work: a blue crab almost ready to molt, to shed its hard shell and start over again with a new, softer shell that will take days to harden up. A bushel of medium size hard crabs may bring a crabber $30 for about 90 crabs. But medium size soft shells like this usually bring $3 each. Do the math.That's $90 for 30 crabs.

Photographs by Michael W. Fincham, drawing courtesy of the Virginia Institute of Marine Science

See all posts from the On the Bay blog