Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

Septic Maintenance Matters for the Chesapeake Bay

It’s almost certainly the most expensive appliance in your home. Like the kitchen sink, it gets used each day. It requires maintenance just like a washing machine or oven. But unlike other home appliances, septic systems are out of sight and out of mind—until something goes wrong, that is.

“If your system fails and you need to replace it, that’s several thousand dollars minimum for a conventional system,” says Water Quality Specialist Andy Lazur. “If you have a good, functioning septic system, that’s going to protect your property value. And most important of all, you're going to protect public health— that is yourself, your family, your neighbors—and also the environment.”

But by the time homeowners notice soggy ground or an offending odor, the damage is often done and it’s too late for minor repairs. The damage can be costly—not just for the 425,000 Marylanders who rely on septic systems, but also for the Chesapeake Bay, which can accumulate nitrogen and other nutrients that flow into waterways and affect water quality. High levels of nitrogen can lead to algal blooms, which can suffocate fish and snuff out patches of Bay grass.

That’s why Lazur offers a variety of webinars, seminars, workshops, and manuals related to septic system care for Marylanders through University of Maryland Extension.

“I would say the vast majority of those homeowners really don't understand their septic system, nor do they really know how to care for a septic system,” Lazur says.

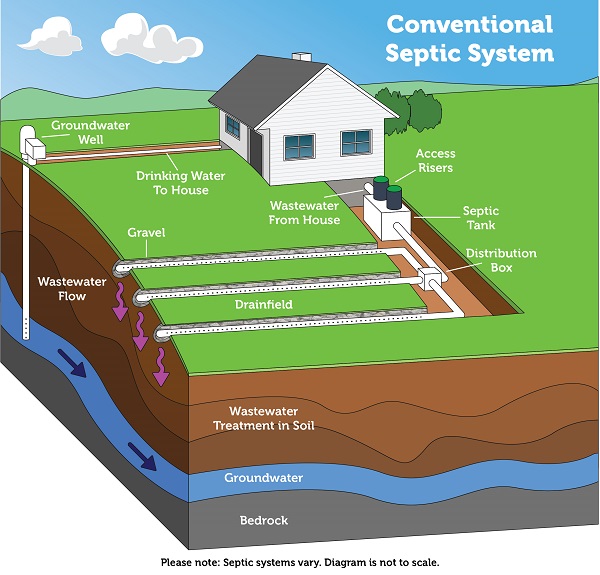

Septic systems treat the so-called black and gray water from a household, including sinks, laundry machines, showers, and of course, toilets. Traditional septic systems contain multiple compartments. In the first, grease floats to the top of the tank, and solid materials sink to the bottom of the tank, where helpful bacteria break down solids in the water. The water between the grease and solid layers flows into a second chamber, where bacteria continue to break down organic particles.

The wastewater then flows through pipes into nearby soil designated as the septic tank’s drain field. Here, any harmful bacteria, viruses, and nutrients are naturally filtered out as the water passes through soil and interacts with bacteria in the dirt. As the water passes down through the soil, it ultimately becomes groundwater or flows into a nearby waterway, re-entering the ecosystem.

“We’re taking advantage of natural processes in the environment,” Lazur explains.

There are many reasons a septic system can fail—clogged pipes, cracks in an improperly installed system, or overloading the system with harsh chemicals—but the result is the same: untreated sewage rich in nutrients and harmful bacteria leaches into the ground and nearby waterways. For coastal homeowners with septic systems near the Bay or along its tributaries, a malfunctioning system can threaten local water quality.

Lazur emphasizes in his workshops and webinars how small actions can help keep septic tanks functional for longer. He encourages people to “think at the sink” when it comes to washing dishes with grease, oils, and food, and “don’t strain your drain” with more water than the septic system can handle at once. Pumping out the remaining solids from a septic tank every few years can also prevent blockages that require costly repairs.

For coastal homeowners, sea level rise and flooding can raise the water table in their septic drain fields, preventing the wastewater in the septic system from draining properly. In areas with high water tables, cutting-edge septic systems labelled as “best available technology” or BAT are often used. These systems are installed in raised mounds and rely on gravity or pumps to move the water through the system. They can also reduce nitrogen and other contaminants in the treated water—reducing nitrogen pollution in the Bay in the process.

“These systems are basically like a miniature wastewater treatment plant in your backyard,” Lazur says. By adding in an aeration chamber, beneficial bacteria use the oxygen flow to convert nitrogen in wastewater into a harmless gas that joins the abundance of nitrogen gas already in the atmosphere. “These units are very effective. The water that comes out of a BAT unit is very clear and essentially odorless. It’s good for advanced reduction of nitrogen, but also can extend the life of a drain field.”

Since these upgrades can be costly, Lazur also connects homeowners to local, state, and federal programs that aim to improve water quality by assisting homeowners with septic system repairs and upgrades. Lazur says Maryland's Bay Restoration Fund is one of the best financial assistance programs available on the East Coast, with more than $16 million given out each year in grants and loans.

He'll even offer suggestions about how to landscape around a septic system to minimize its appearance without affecting the septic system’s performance.

“The most common question I get is probably, ‘Can I landscape my septic system or a component of my system?’ If they have a sand mound which is elevated, it's just a two-to-four-foot-tall mound in their backyard or front yard,” Lazur says.

Visit the University of Maryland Extension website for additional resources about maintaining or upgrading septic systems. Check for upcoming webinars or workshops here.

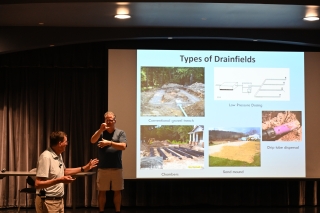

Top left image: Andy Lazur presents septic system information at a workshop. Photo: Madeleine Jepsen, MDSG

See all posts from the On the Bay blog