Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

Rip Current Safety

Every year, lifeguards in the U.S. rescue tens of thousands of people from rip currents, the sudden, unexpected, and strong underflows that can pull swimmers out to sea. Still, about 100 people drown annually because of rip currents -- many more than those killed annually by sharks.

Maryland's Ocean City beach annually recorded more than 4.5 million beach visits in recent years and its lifeguards have made more than 2,600 rescue and prevention attempts. The patrol estimates more than 90 percent of those rescues are the result of rip current conditions that are poorly understood by swimmers.

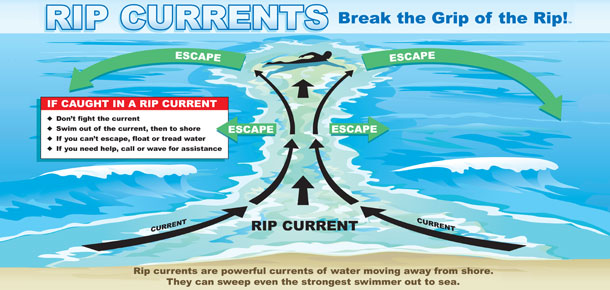

Rip currents form when waves and water pile up near the beach and suddenly seek a way back out to sea, forming rough plumes and taking swimmers for a wild ride. If swimmers panic and try to swim back toward shore against the current, they may become too fatigued and panicked to make it back alive. Rip currents can travel up to eight feet per second, faster than even Olympic champions can swim.

Maryland Sea Grant carried out a public education campaign to inform swimmers about rip currents in conjunction with the U.S. Lifesaving Association and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA.) In 2006, 130 new signs were put up in Ocean City and Assateague Island warning beachgoers about the danger.

The rip current signs display a simple graphic using green arrows to show swimmers how to escape the dangerous grip of rip currents. The key safety message: do not try to swim against a rip current to get back to the beach. To escape, swim toward its edges (perpendicular to the direction of the current’s flow.) This phrase sums up what to do if you're caught in a rip current: WAVE, YELL, SWIM PARALLEL.

Download a pdf of the rip current sign.

Download a pdf of the bilingual version.

Learn more

- Read Keeping Swimmers Safe, an issue of Chesapeake Quarterly, Maryland Sea Grant's magazine, about coastal water safety.

- Find out about research supported by Maryland Sea Grant to model how rip currents form by using cameras to observe the currents as they happened.

- Visit NOAA’s website on rip currents, which contains additional information about the campaign to educate swimmers.

Maryland Sea Grant Video

A Maryland Sea Grant video describes the Ocean City lifeguards who save swimmers from drowning. They can describe first hand the danger of rip currents.