Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

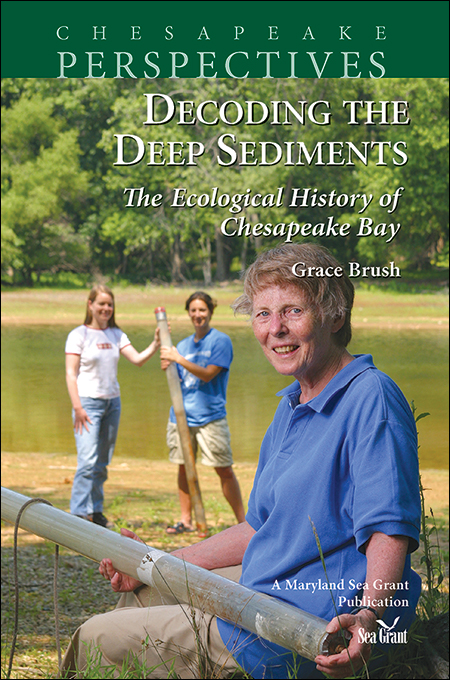

Bay History

The Chesapeake Bay has its beginnings in the ancient Susquehanna River valley. More than 18,000 years ago, geologists believe, the Susquehanna flowed directly into the Atlantic Ocean, with the valley surrounding it meandering through the continental shelves.

As glaciers began to shrink, sea level began to rise, and the waters of the Atlantic moved up into the Susquehanna valley. By about 10,000 years ago, these waters had stretched up to what we now know as southeastern Virginia. By 3,000 years ago, ocean waters had reached what is now Havre de Grace, Maryland, where the Susquehanna meets the Chesapeake Bay today. The river’s fresh water mixed with salt water flowing northward from the ocean to form an estuary stretching south to the location of modern-day Norfolk, Virginia.

In the more recent past, the Chesapeake Bay played a part in some notable events in the history of Maryland and the nation.

The mouth of the Bay, along Virginia’s shores, served as a backdrop for the 1781 Battle of the Chesapeake during the Revolutionary War. French and British fleets collided in a battle that proved to be a crushing defeat for the British at the port of Yorktown.

In the War of 1812, the Chesapeake Bay was a crucial location for both American and British troops. For the United States, the Bay provided a water passageway to the nation’s capital of Washington D.C., and to a prominent harbor in Baltimore, where commercial ships offloaded their goods. This also gave the British easy access to enemy strongholds and enabled them to sail from their location just south in Norfolk, Virginia, invade and burn Washington, and bombard Baltimore. Their forces were repulsed in Baltimore, and later at battles in New York and New Orleans, leading to their defeat.

The Bay also played a role in the early history of African Americans in our region. Slavery began in Maryland in the early 1600s, where there was a rising economy based on growing labor-intensive tobacco.

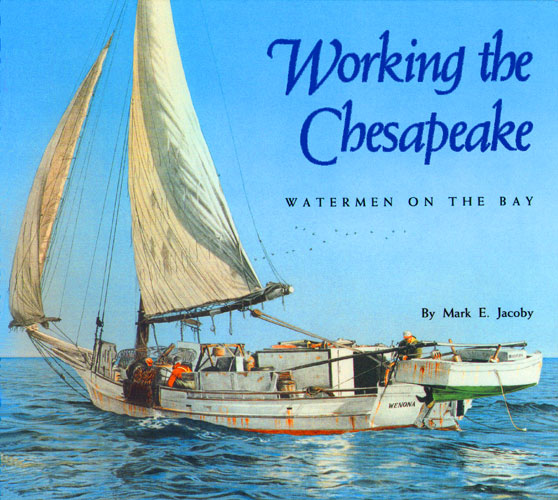

By the 1790s, the tobacco market had altogether collapsed because of overplanting, and many blacks began working on ships through the Bay. By 1796, black merchants were defined as “citizens” by the government through Seamen’s Protection Certificates, furthering their view of sailing as a way to economic opportunity and self-determination.

African Americans have been harvesting and sailing the Bay since first coming to its shores, but stories particular to their lives are not as well known. To chronicle this aspect of Bay culture, Maryland Sea Grant produced two newsletters about African Americans working in the Chesapeake Bay in the mid-twentieth century — one about three independent watermen who harvested oysters from their own boats, and another about men who hauled menhaden into huge nets for commercial ships while singing chanteys. You can read those stories here: Black Men, Blue Waters and Menhaden Chanteys: An African American Maritime Legacy.

The 1800s marked the advent of science related to the Chesapeake Bay. Early research focused on the Bay’s fisheries, such as William K. Brooks’s influential work on oysters and their reproduction. As Bay science grew in the mid-twentieth century, so did the number of research institutions and educational programs surrounding the study of its waters and species.

By the 1970s and 1980s, the decline of Bay species and increase in runoff had caused a decline in the Bay’s health. Researchers worked to understand the causes and to figure out how to reverse the trend. Their findings have been critical to efforts to restore the watershed that continue today. More recently, concerns over rising water and air temperatures have led scientists to begin to investigate how climate change will affect the Bay.

Maryland and Virginia sea grant programs established the Mathias Award in 1989 to honor several of the premier Bay scientists whose outstanding work has helped us better understand this body of water recognized as a national treasure.

Photograph by Skip Brown