Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

Schmutz in the Susquehanna: Researching Lyngbya cyanobacteria

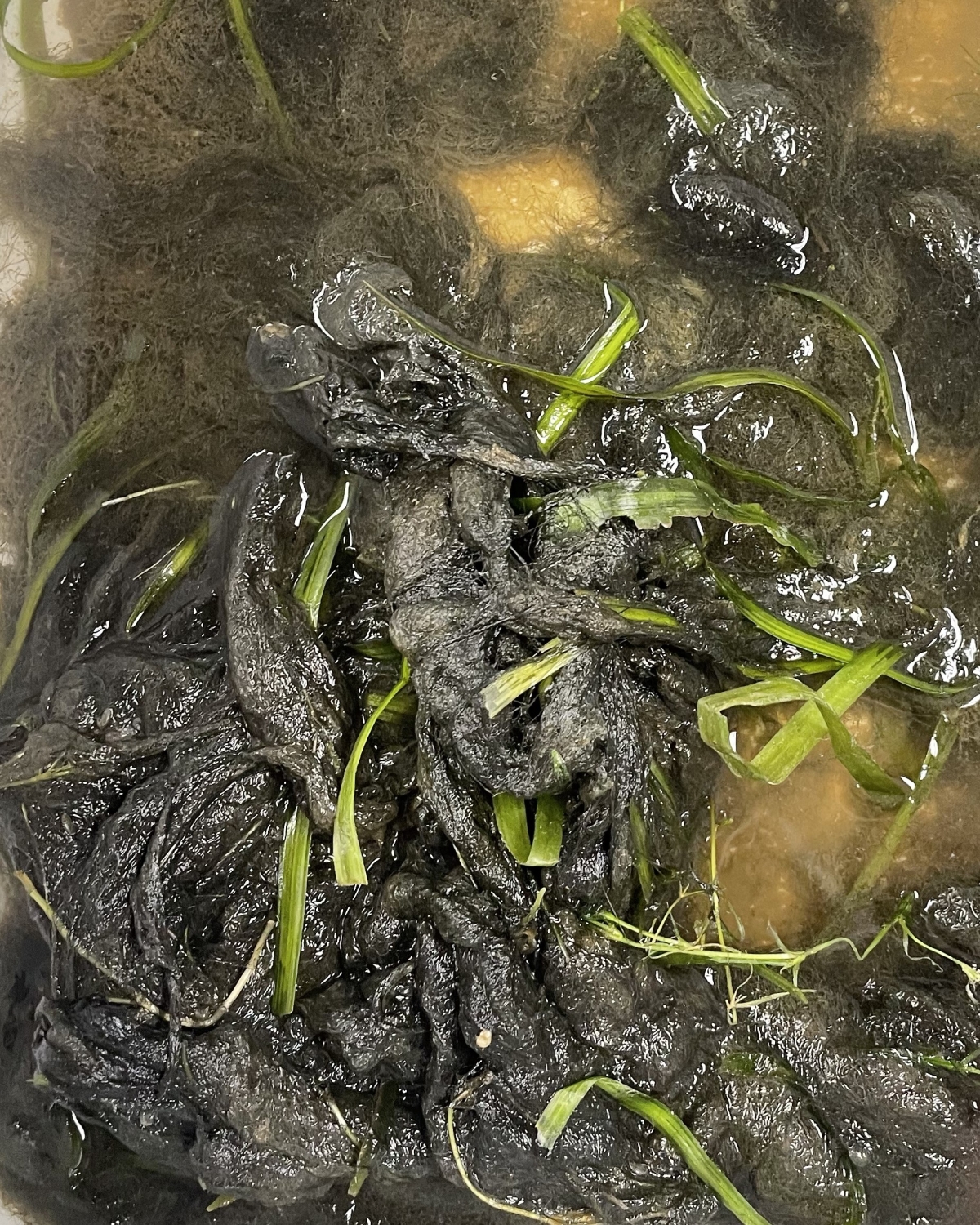

You may have heard the word “schmutz” used when cleaning up something unappealing, but you probably haven’t heard the word used to describe an organism. But that is what Lyngbya is: schmutz! This stringy type of cyanobacteria can be toxic and irritating, and it gets everywhere. A few people have even described it as “gross drain hair,” and sailors used to refer to it as “Mermaid’s Hair.” Here at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science Horn Point Laboratory, we find schmutz intriguing!

My advisor, Dr. Judy O’Neil, investigates Lyngbya’s presence in submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV) beds in the Chesapeake Bay. She is particularly interested in the upper Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Susquehanna River, an area known as the Susquehanna Flats. Although observations indicate Lyngbya has been growing there in increasing abundance for about a decade, its interactions with SAV plants, biogeochemistry of the sediments, and general ecology of Susquehanna Flats has not been fully investigated.

The Susquehanna River is the largest tributary of the Chesapeake Bay. The water quality and health of the river directly impact the Bay's health. At the mouth of the Susquehanna River and south of the Conowingo Dam sits the beautiful SAV bed of the Susquehanna Flats.

This SAV bed was wiped out in 1972 by Tropical Storm Agnes but had an astounding recovery in the 2000s. As a point of reference, the bed covered around 50 square kilometers (about twice the area of the John F. Kennedy Airport) at its most recent peak in 2008. The Susquehanna Flats SAV bed filters incoming sediment and nutrients from the Susquehanna River’s discharge. It also serves as great habitat for fish, crabs, and many other species.

Some cyanobacteria species, such as Lyngbya, have been increasing on the Flats since 2004. Cyanobacteria are photosynthetic bacteria that live both in sediment and in the water, and some can create their own nitrogen from the atmosphere when the environment does not provide them with enough nitrogen. This is important for their growth, since cyanobacteria require nitrogen for growth just like plants do.

Lyngbya grows on the bottom of the Susquehanna Flats. Through rapid photosynthesis, these bacteria release gas bubbles, which get trapped in the bacteria’s hairy filaments and cause Lyngbya to rise to the water’s surface. There, it may compete with SAV for sunlight and spread to other locations. Due to the toxic nature of Lyngbya, it may pose a threat to the surrounding environment. How much of a threat? That is what we are working on figuring out!

Lyngbya may cause a variety of problems for the Susquehanna Flats. For starters, its mat-like growth patterns may block SAV from sunlight by physically covering the plants and floating to the surface. Lyngbya’s nitrogen-creation capabilities may also be altering the Flats from a nitrogen sink to a nitrogen source, making it less efficient as a nutrient filter for the rest of the Bay. Some of our early findings show that Lyngbya produces a neurotoxin that may be detrimental to other species in the Susquehanna Flats food web, but further investigation is required.

Humans enjoy fishing, hunting, and boating on the Susquehanna Flats, but no one has studied Lyngbya living in the waters where people like to spend their time—yet. A crucial first step to answering these questions is to correctly identify the exact species. I will use DNA analysis technology to learn the genetic code of the Lyngbya, so if this species shows up elsewhere, we can better pinpoint options for mitigation and management measures.

Currently, scientists are reclassifying different types of cyanobacteria. Some Lyngbya have been reclassified as Microseira and some have remained Lyngbya. Will the Lyngbya in the Susquehanna Flats remain Lyngbya, or will it need to be reclassified? Stay tuned: Hopefully, we will soon know what this exact species identification is!

Top left image: Shayna Keller examines SAV in the Susquehanna Flats during fieldwork. Photo: Judy O’Neil

Sign up to receive email alerts about new posts to the Fellowship Experiences blog

See all posts to the Fellowship Experiences blog