Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

Who Volunteers for the Watershed Stewards Academies?

Based on a recent survey, my advisor, a colleague, and I have found that people who volunteer in environmental groups are unlike the average citizen.

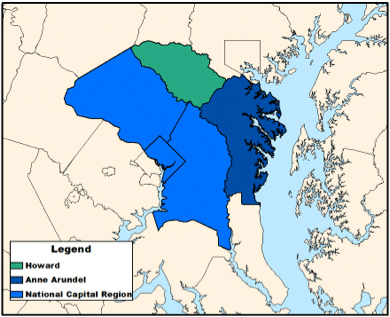

We surveyed people who participated in training offered by Maryland's Watershed Stewards Academies (WSAs), which offer volunteers in-depth and intensive courses on watershed restoration and stewardship in the Chesapeake Bay region. The goal of the WSAs is to provide volunteers the background and support to become leaders and engage members of respective communities, so that they may lead a grassroots-level effort to improve the health of their watersheds and sub-watersheds. At the time of our data collection, there were three established WSAs in Maryland: Anne Arundel County’s, founded in 2009; Howard County’s, founded in 2012; and the North Capital Region’s, which was founded in 2011 and encompasses Montgomery County and Prince George’s county in Maryland and Washington D.C. (Each area is pictured in Figure 1).

|

| Figure 1: Established WSA Programs in Maryland. Credit: William Yagatich |

Within the field of sociology, there is a great deal of interest in knowing how and why people are mobilized to participate in social movements and causes. In particular, we are interested in how and why people would participate in an environmental restoration group. To know more about how and why some people become civically engaged, first we need to know who volunteered with the WSAs.

To shed light on who participates in the WSAs, we distributed an online survey to everyone who has attempted the training at one of these WSAs (regardless of whether he or she completed the training) and has kept his or her contact information current with the WSAs. The survey took about 15 to 20 minutes to complete. It asked respondents questions about their experience with the WSAs and some personal background information that is typical of much sociological research. In total, we asked 274 people to complete the survey and received 154 responses, finishing with a response rate of about 56 percent. About half of the participants of each WSA completed the survey.

What we have found so far is that the typical WSA member is distinct from the general population of the areas of Maryland and Washington D.C. highlighted above in Figure 1. In fact, it would not be enough to say we found small differences between the stewards and the general population they are meant to represent. When comparing our sample of survey participants to the general populations of Howard, Prince George’s, Anne Arundel, and Montgomery Counties in Maryland and of Washington D.C., we found that the respondents, as a group, have greater proportions of individuals who are white, female, retirement age, and well educated. These differences were statistically significant. Similarly, when we compared our survey sample with national samples, we find that the WSA members are much more politically liberal and they are also much more civically engaged (see Table 1).

Table 1: Civic Activities of WSA Stewards versus National Population

In other words, the demographics of the survey respondents don’t reflect the diversity of communities found in the areas served by the WSAs. These results are important for anyone interested in civic engagement and volunteerism because social scientists have found similar demographic trends for volunteer groups in general, but much less is known about who participates in volunteer environmental restoration groups. Why we see this demographic composition within the WSAs would require further research beyond the scope of this initial survey. At the same time, for environmental volunteer organizations such as the WSAs, these findings may suggest a need for the adoption of new strategies and means of outreach to recruit a more diverse set of volunteers. In fact, the WSAs have recently begun to reach out to faith-based organizations, so it remains to be seen if efforts like these will help to ameliorate this gap.

|

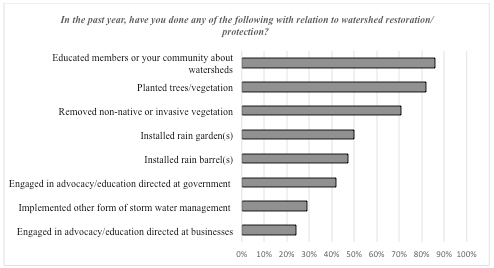

| Figure 2: Watershed Steward Activities in the Past Year. Credit: William Yagatich |

The survey also asked about what kinds of environmental outreach and restoration work the WSA members had done. We found that most respondents engaged in stewardship through community education, while nearly as many said that they participated in more hands-on projects, such as planting trees and other vegetation (Figure 2). Nearly half of all stewards also helped to install rain barrels and rain gardens in their local communities. It is interesting to see the members of the WSAs are engaged in multiple types of stewardship and that there is no one dominant approach to their work as stewards.

In the next stage of our project, we will be doing in-depth interviews with a sample of the WSA participants who responded to the survey. In these interviews, we hope to learn more about how they learned of the WSAs and became involved with them and what sort of impact on the environment they perceive they have made. While we have some idea of the answers to these questions based on the survey results, they are a poor substitute for actually interviewing the volunteers themselves. By the end of the research project, it is our hope to better answer, “How effective are stewardship groups at reaching out to communities and improving the environment?”

See all posts to the Fellowship Experiences blog