Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

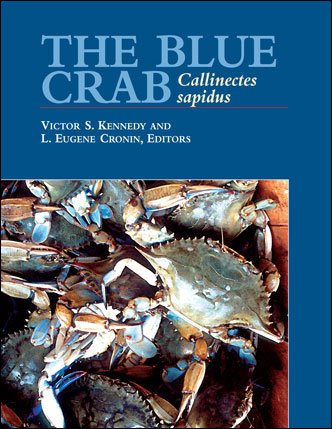

The Blue Crabs of November

Roger Morris knew autumn crabbing would end early in 2017. Last year the legal crabbing season lasted until 10 days before Christmas. This year it would close down three days before Thanksgiving. So November would be his best shot at a good year.

The Great Migration. Autumn can be busy time for blue crabs and those who would catch them. As the days shorten and the weather cools, female blue crabs start scuttling southwards and male crab head for deeper waters. And watermen start resetting their lines of crab pots, trying to guess when and where the crabs will be moving during their down Bay migration.

The Great Hunt. Morris has made a couple guesses about where blue crabs might be moving -- and he's bet more than 1,000 pots on his thinking. He's placed more than 500 pots in Bay waters south east of Lower Hooper Island, and every Monday, Wednesday and Saturday he fishes them to see how many crabs they caught. He also plunked another 500+ pots further south, down in Tangier Sound near Bloodsworth and Smith Islands. He and his crew fish those pots every Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday.

Do the Math. With travel time figured in, the job of fishing 500+ pots in a day works out to a fishing rate of more than 60 pots an hour, better than a pot a minute. The key to fast fishing on an ever-moving boat is teamwork.

Dancing with Crabs. Fishing crab pots is a form of dance with everybody moving in rhythm with their partners, keeping time to the unstoppable movement of the boat towards the next buoy and the next pot. As dances go, it's not a ballet, more like a waltz with partners repeating the same steps over and over. Perhaps it's most like a swing dance with quick whirling moments of catching and releasing. Roger hooks the buoy line, cranks the pot upwards, and swings it aboard. Doodle Patterson does the catching and turning, the rebaiting and the throw back.

Man in the Middle. In this three-partner flow, Doodle is the player with the most to do in the shortest time. Think of a second baseman in the middle of a double play: he has to make the catch, make the turn, and throw to first. Doodle has to catch the pot, turn it upside down, shake the crabs onto the culling board, rebait the pot, and throw it back in the Bay.

Crab Feast. To attract tomorrow's crabs into 500 pots, Doodle restocks each pot with fresh bait, in this case with a handful of razor clams. Crab potters also use oily strips of fresh eel meat or menhaden. Some think frozen menhaden works best. Crabbers who work with trotlines also try turkey necks and meat from the lip of a bull. Recreational crabbers, of course, favor chicken necks.

Legal Seafood. Frank Mand runs the boat's culling board, keeping everything legal by spotting and tossing undersize crabs back in the Bay for next year's harvest. He packs the jimmies (male crabs) and sooks (female crabs) in tall plastic trash cans.

An Autumn Surprise. As the pots come swinging on board, Morris and his crew keep finding only a few crabs in most pots. Even Roger's dog Renny looks concerned. Where are the rest of November's crabs?

A Waterman's Dilemma. The warm November weather makes for pleasant but less profitable crabbing with so many crabs waiting longer before heading south and ending up in Roger's 1,000 pots. An early end to the season will mean less time to catch crabs. And a warm November will mean fewer crabs to catch.

Closing Time. The early closing to the crab season came as no surprise to Morris who also works on Maryland's annual blue crab survey, providing the boat and crew and the dredge. When last year's winter survey showed a drop in the number of juvenile crabs in the Bay, Morris got to worry all year that there would not be as many large crabs come November.

Break Time. As the captain heads his boat eastward to check on his lines of inshore pots, his crew and his dog take some well-earned down time.

Payoff Time. His bet on inshore pots pays off for Morris, when he starts finding more crabs and larger crabs. These will go to Clayton's Seafood in Cambridge for picking and packing and shipping. Their meat will end up in crab salads, cream of crab soup, and classic Maryland crab cakes, perhaps as a side dish to go with the turkeys of Thanksgiving and Christmas.

Homeward Bound. The day is not done for Roger Morris or his dog. There's still the 30-mile drive from Wingate to his buyer, Clayton's Seafood in Cambridge. And the 30-mile drive back home.

Closing the season on November 20 will let more female crabs reach the southern Bay this year, and next spring many of those who survive the long trek will each release a million or more crab larvae into the Bay's waters. With the right luck and the right weather, a small percentage of those new crabs will eventually make the great migration north into Maryland waters. Where Roger and Doodle and Frank and a big black dog will be waiting for them.

See all posts from the On the Bay blog

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)