Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

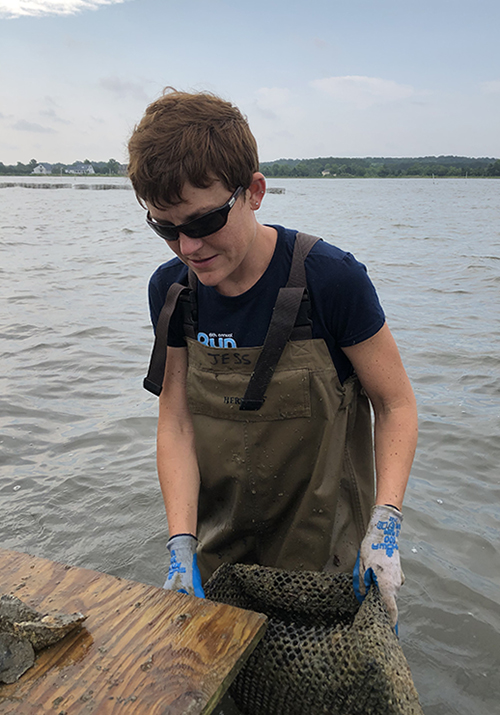

Who Runs the (Hatchery) World? Increasingly, women are behind the microscope and in charge of the tanks

There used to be a photo hanging at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science’s Horn Point Oyster Hatchery. The image shows four women who worked in the hatchery in the 2000s standing in front of a large truck emblazoned with the words: Powered by Estrogen.

A decade after the women snapped the photo at the Punkin Chunkin’ World Championship in Delaware, those words are truer than ever. Not just at Horn Point, where Stephanie Tobash Alexander leads a largely female staff to produce the billions of oyster larvae that they use to seed the Chesapeake Bay, but also throughout Maryland and Virginia.

Hatchery work is demanding, meticulous, and at times physically unrelenting. The work forces are often small, just five or six employees, and the to-do list is unforgiving. These teams must successfully breed and raise billions of baby bivalves. They culture the oysters’ food (algae), sterilize the tanks, condition the parent oysters, or broodstock, and troubleshoot when issues arise, which they often do in the fragile lives of tiny oysters.

“I never really thought that I’m paving the path for a future of women in charge,” said Alexander, who has worked at the Horn Point Oyster Hatchery in Cambridge for 20 years. She was promoted to director last year and still keeps the “Powered by Estrogen” photo in her office. More than half of the summer interns at the Horn Point hatchery are women undergraduate science majors or graduate students, she said. “In the hatchery environment, you respect hard work, and as long as you’re a hard worker, it doesn’t matter what the gender is. But women are already in the hatchery environment, and it’s kind of natural for us to be doing this.”

Maryland has four stand-alone hatcheries. Two, Horn Point and the private enterprise Hooper’s Island Oyster Company, have female hatchery managers. The third, Piney Point Aquaculture Center, run by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources, has a male manager, but a former Horn Point intern, Amanda Ault, is the second-in-command. Trained as a biologist, Ault came to the hatchery after working at a nearby oyster farm. The fourth, Morgan State University’s Patuxent Environmental & Aquatic Research Laboratory (PEARL), was managed until recently by Rebecca Borgert. Its hatchery staff has been about 70 percent women in recent years, according to Jon Farrington, PEARL’s facility manager.

In Virginia, women run all three of the hatcheries connected to the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS), as well as the four month Oyster Aquaculture Training Program, known as OAT, that trains its interns for industry jobs. Of the seven large private hatcheries, all but one report either to a woman at the helm or one in a crucial second-in-command spot.

It hasn’t been one program or one push that’s brought women to hatcheries, according to many of the women interviewed for this article. It’s happened organically, either through a charismatic professor or an interesting internship opportunity. And it wasn’t sudden, either, but instead a gradual evolution as more women enter marine science.

“I don’t think I thought too much about it at the time, but when I began working at the oyster farm, it was super-encouraging to remember that at Horn Point, it was all women,” said Ault, who was often the only woman lifting cages on her shifts at her oyster farm job. Though she became a supervisor at the farm in just two months, Ault said, she was glad to return to a hatchery where “I can use my degree more. I get to think through problems more.”

That’s a trend nationwide, said Kenneth Riley, a marine ecologist with NOAA’s National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science. He’s part of the Coastal Aquaculture Citing and Sustainability Program, an initiative to identify where to locate aquaculture nationwide.

“I find hatcheries have been the one area, whether on the commercial side or research side, where women are operating and running things,” he said.

Women, Riley said, come to hatchery work from multiple avenues. Some come from research institutions, like University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science and VIMS, which prepare interns for work in the industry. Others learn skills through Sea Grant Extension educators or through growing up in their family businesses. Some hold PhDs. Others have a bachelor’s degree in a related field. Riley said he doesn’t have numbers for graduation rates of women in related fields, but thinks that hatchery work is a “major growth sector” for women in marine and environmental science.

VIMS and Horn Point are not the only places seeing growing interest in hatchery work from their female students. Dale Leavitt ran the Woods Hole Sea Grant education program and is now the aquaculture extension specialist at Roger Williams University in Rhode Island. He said recent graduates have taken management positions at large hatcheries, such as Island Creek Oysters in Duxbury, Massachusetts, and Louisiana’s Michael C. Voisin Oyster Hatchery. They’re all women.

“We have been really successful in placing our students into hatchery management operations all up and down the coast, and I would say 100 percent of them are women,” Leavitt said. “We have a couple of guys working on farms, but in terms of hatcheries, it’s all women.”

Karen Rivara, president of the East Coast Shellfish Growers Association and of the Aeros Cultured Oyster Company in Long Island, New York, has been a hatchery manager since the 1980s. Women, she said, were always there, but not always as equals. At one job, she found the male business partners had meetings without her and that a promised hourly raise had not been added to her check. In both cases, she spoke up, and things improved. The younger generations are not only unbothered by women in management, Rivara said, but they also see managers like Alexander and Jessica Small, associate director of the Aquaculture Genetics and Breeding Technology Center at VIMS, through their training. That encourages women to believe there’s a future in the industry, she said.

“I don’t think there’s a huge barrier for us,” Rivara said of women getting into hatcheries. “Women are solidly moving through the industry, and you’ll probably see more women running hatcheries.”

One reason we may see more women running hatcheries is that we are going to see more hatcheries in general, according to some in the industry. Maryland Sea Grant Extension Specialist Don Webster has been advocating for more hatcheries in the Chesapeake Bay, particularly in Maryland, for at least a decade. Maryland’s only private hatchery now is Hooper’s Island, and it opened only within the past few years. A foundation is planning for another one on Tilghman Island. But Webster remembers when Maryland had several, which seeded a small leased-bottom oyster industry in the 1970s and 1980s before many closed because they could no longer afford to operate. Those were run mostly by men, Webster said.

The tide began to turn for oysters, and hatcheries, in the early 2000s, when Maryland and Virginia were considering introducing an Asian oyster species, Crassostrea ariakensis, into the Chesapeake Bay and needed to raise disease-resistant native oysters as a control group for scientific experiments. Private hatcheries that had long since turned to clams began working with oysters again; in the end, the states and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers decided not to introduce a non-native species and instead stick with Crassostrea virginica, the native oyster. Oyster aquaculture got another boost when Maryland changed its law in 2009 to allow oyster farming in every county in the state. In both states, more oysters were showing up on menus at high-end restaurants, and more restaurants opened primarily to showcase the Chesapeake oysters.

The changes in Maryland and Virginia mirror some increases nationwide. According to the USDA’s most recent Census of Agriculture, total sales of aquaculture products in 2018 was $1.5 billion, a 10.5 percent increase from 2013. Mollusk sales were $441.8 million, up 34 percent from 2013, with oysters accounting for 64 percent of those sales.

The aquaculture industry needs hatcheries not just to feed small oysters to the expanding commercial sector so the animals can become larger and marketable. It needs a diversity of salinities in which to grow the oysters. Oysters need a precise mix of fresh and saltwater to grow. Too salty, and they can succumb to diseases and parasites. Too fresh, and they won’t grow. If Cambridge gets a lot of rain, as has happened, production at Horn Point will slow, and Alexander may call a colleague in Virginia to procure oysters. Similarly, colleagues in Virginia sometimes reach out to Maryland. A few years ago, Oyster Seed Holdings, a hatchery in Virginia, lost many of its oysters when a state construction project worsened water quality at the exact time when the hatchery was trying to breed the animals.

For as long as women have been running hatcheries, many say, their colleagues have been musing about what makes women well suited to the job. What some women hatchery managers bristle at is the notion that women are better at the job because it is essentially a reproductive task—to make offspring and keep them alive.

“The ‘we’re more capable of nurturing’ line—frankly, I resent that,” said Small, associate director of the Aquaculture Genetics and Breeding Technology Center at VIMS. “Why women get those jobs, and hold them, is their attention to detail, their ability to multitask, their organizational skills. In commercial hatcheries, and a research hatchery like ours, it’s fast-paced, there’s a lot to keep track of. We are a really resilient gender. You have to get the work done, and if you don’t then there’s huge consequences.”

Small, like Alexander, says she didn’t set out to be a pioneer in the industry, but she’s proud of her record of helping to seed it with women marine scientists. Female graduates of VIMS include Kasey Bond of Oyster Seed Holdings, Inc., on Gywnn’s Island in Virginia, and Imani Black of Hooper’s Island Oyster Company. Small said others in the industry are often calling, asking if they have trained anyone new.

“The ladies at VIMS are my biggest role models,” said Black, who thought she’d study tropical biology until she discovered how much she enjoyed hatchery work during her internship. “There are so many women in that one department. Right there is a great example of women really trying to get the job done.”

Hooper’s Island Oyster Company hatchery manager Natalie Ruark, who graduated from Randolph-Macon College with a biology degree, said she and Black’s all-female team rely on each other as well as advice from Alexander and the other women in the industry.

“It’s been my experience that women can fit in anywhere in aquaculture,” Ruark said, “but you really have to want it.”

Photo, top left: The women of Horn Point Oyster Hatchery pose in front of handpainted lettering at a festival over a decade ago. Some of them have moved on to other jobs, but women remain in charge of the hatchery as well as in many other jobs there. Left to right: Emily Vlahovich Hagy, Angela Padeletti, Claire Rounsaville Houchens, and Stephanie Tobash Alexander. Photo courtesy of Stephanie Tobash Alexander

See all posts from the On the Bay blog