Spotted Salamander Symbiosis: Content Primer

Modern Research, Part 1

In 2011, Ryan Kerney, now an Assistant Professor of Biology at Gettysburg College, started to ponder century-old suspicions of symbiosis about one such vernal pool denizen, the spotted or yellow-spotted salamander, Ambystoma maculatum.

Spotted salamanders, commonly found from Maine to Georgia and extending into the Midwest, are difficult to sight since they are strictly nocturnal; and, after mating season, they spend most of their time underground in the quiet confines of small mammal burrows and tunnels. These salamanders, which belong to a group known as mole salamanders, make the most of their ability to burrow under leaves and logs in search of food, like earthworms and slugs. In early spring, amid cool temperatures and rainy nights, “spotteds” begin their annual migration to vernal pools to start the reproductive process. At its peak, hundreds of these salamanders trek to the pool’s icy cold waters. Male salamanders leave behind a spermatophore, or packet of sperm, attached to a stick or leaf.

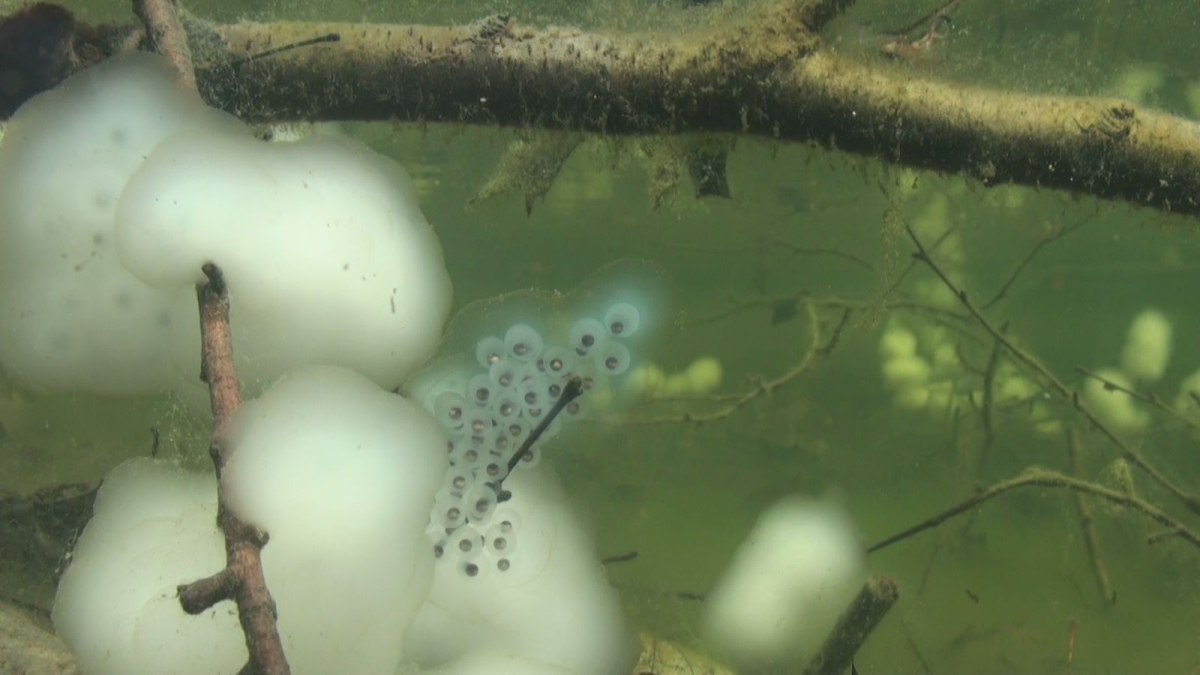

Females pick up the packets of sperm and fertilization occurs internally. But, this is not the part of the lifecycle that caught Kerney’s eye. Dating back to 1888, Tulane University biologist Henry Orr documented his findings — a spotted egg case, a whitish thick gelatin, turned greenish during development, presumably because it was covered with a species of algae. Orr suspected a symbiotic relationship. In his paper Note on the Development of Amphibians, he stated:

“I have not discovered how the algae enter the membrane, nor what the physiological effect they have on the respiration of the embryo, but it seems probable that in this latter respect they may have an important influence.”6

Orr’s hunch was a good one. A spotted salamander egg case is dense and can house over 100 individual eggs. In a vernal pool with little water circulation, it would be difficult for embryos to get oxygen and food (since they have little yolk)

By the 1940s, it was widely accepted that these organisms had developed a symbiotic relationship consisting of algae colonizing the egg case of the spotted salamander with each being a potential beneficiary.7

Nomenclature Notes

Note the different spelling of the genus name of the salamander (Ambystoma) and the species name of the algae (amblystomatis). Ambystoma, a misspelling by Swiss naturalist Johann Jakob von Tschudi in 1838, was intended to translate into “blunt jaw” when he described the genus of what is known as mole salamanders. He repeatedly used the misspelling in publication; and, by taxonomic rule, the original spelling stands. However, the correct spelling amblystomatis (note the addition of l), was given to the name of the symbiotic algae in 1927 by Lambert Ex Printz.8