Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

Food Web

Think of the Chesapeake Bay ecosystem as one big web. That web is made up of countless organisms — including animals like fish and crabs, plants like eelgrass, and smaller organisms like algae. And they're all interacting with each other. Some get eaten. Others do the eating.

The end result of all this interacting is that energy gets passed throughout the ecosystem. In this case, energy means carbon. Or, more particularly, molecules that contain carbon, such as sugars, proteins, and fats. In these interactive diagrams, you can see how organisms are connected through the energy (carbon) they pass along as they eat or are eaten.

Life in the Food Web

Roll your mouse over a trophic level name, species name or species image below to find out more about it.

Energy in the Food Web

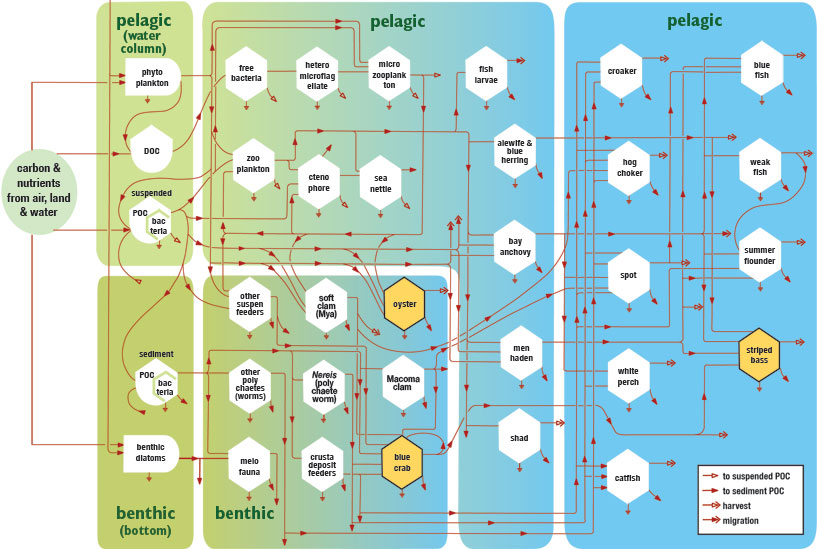

This diagram shows a mid-Chesapeake Bay food web (salinity 5-20 parts per thousand). Roll your mouse over the orange polygons below to highlight who eats whom. This chart tracks carbon, the raw material for energy, as metabolism breaks down organic matter. Much of that energy is lost, but carbon is continually recycled.

Credit

We adapted this energy network from a diagram developed by Robert Ulanowicz, a scientst at the Chesapeake Biological Laboratory, which is part of the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science. For more on Ulanowicz’s work, see this article, A Scientist for All Seasons.

Steps in the Food Web

Each step in the Bay's food web is unique — and also plays an important role in the ecosystem. Here, we trace those steps from the bottom of the web to the top. That means us.

Lower Food Web

Organisms in the lower food web are usually small — in fact, most are so small they can't be seen with the naked eye. But that doesn't mean they're not important. These organisms produce the building blocks of all Bay life.

- The Bay's lower food web organisms play a number of roles in the Bay. Those include:

- Phytoplankton, which include algae like dinoflagellates and diatoms, capture energy from the sun. They do that through photosynthesis, turning carbon dioxide from the air into sugar, or glucose. Without these organisms, all of the Bay's animals would starve.

- Phytoplankton also produce oxygen, which all animals need to breathe.

- Small bacteria help to decompose Bay organisms once they die. By decomposing the remains of dead fish or algae, bacteria capture a lot of carbon that would otherwise go to waste. Think of them as the Bay's recyclers.

Middle Food Web

The Bay's middle food web includes small animals, such as worms or jellyfish. But also many fish species like menhaden. Think of these organisms like a bridge — they take the energy produced by the lower food web and make it available to the top food web.

Some of the jobs done by the middle food web include:

- Oysters and clams filter algae out of the water. This helps to keep the Bay clean. But it also helps to turn algae into food that bigger animals can eat.

- Small animals called zooplankton, which include tiny crustaceans known as copepods, are the Bay's grazers. They swim through the water, eating smaller organisms. Zooplankton are important for keeping algae from growing out of control in the Bay.

- But without jellyfish and many fish, which eat zooplankton, the Bay's grazers might eat all the algae in the estuary — not a good plan for the long-term health of the ecosystem.

- Some middle food web animals, such as crustaceans and polychaete worms, also help to decompose dead organisms.

Top Food Web

The top food web is where all of the energy that flows through the Chesapeake ecosystem stops (before being recycled). Here's how:

- Top predators like striped bass hunt for schools of smaller fish, such as menhaden or Bay anchovy.

- Other fish, such as croaker, hogcatcher, spot, white perch, and catfish, also eat animals that live on the Bay's bottom. Those include worms, clams, and crabs.

- These top animals also provide food and income for people who live around the Bay.

How Do Food Webs Work?

A microscopic view of calanoid copepods, a type of zooplankton, in a water sample from Baltimore's Inner Harbor.

It all begins when small photosynthesizing organisms, called phytoplankton, capture the energy from sunlight and store that energy in carbon molecules. Then, those organisms get consumed by bigger ones, which get eaten by even bigger organisms. And so on up to large animals like striped bass or crabs — even people.

Without a stable food web, much of the Bay ecosystem would collapse. Here are some challenges facing this complex network:

- When predators become rare, their prey can multiply. Sea nettles, for instance, eat jellyfish-like animals called ctenophores. That's good because ctenophores eat fish larvae and other important organisms. To keep ctenophores from eating too much, you need to have lots of sea nettles in the Bay — no matter how bad their stings are.

- But in some cases, important predators might not have enough prey to eat. Striped bass, for instance, depend on smaller fish called menhaden for their survival. But fishing and other pressures have decreased the number of menhaden in the Bay. So to help striped bass in the Bay, you also need to help menhaden.

- Some rungs in the Bay's food web have almost disappeared entirely — oysters and fish called shad were once common around the Bay, and now they're hard to find. If they vanish completely, all their connections to other organisms will be lost, too.

These challenges are important to the health of the Bay. But they're also important for many people who depend on the Bay and its watershed for food, clean water, and recreation.